|  |  |  Editorials | Environmental Editorials | Environmental

Keeping a Happy Coast Healthy: One Man's Quest to Save His Little, Fragile Corner of Mexico

Mike Hale - Monterey Herald Mike Hale - Monterey Herald

go to original

November 14, 2010

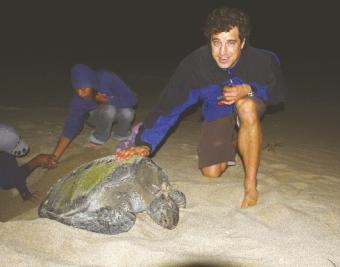

| | Davison Collins, right, on sea turtle conservation patrol at La Gloria, the University of Guadalajara's sea turtle conservation camp. (Tierralegre) |  |

Davison Collins tried to leave this happy coast ... once. He didn't get far, pulled back by a vortex of sun, sand, culture and natural beauty along a stretch of land the Mexicans call Costalegre.

Like many other transplanted Americans, Collins has a deeply personal connection with this coconut-palm-dotted, wildlife-rich region in the Mexican state of Jalisco — an area that remains largely unspoiled, undeveloped and undiscovered.

Collins, 39, is one of several eager protectors of this coastal zone between fiesta-driven Puerto Vallarta to the north and the blue-collar port city of Manzanillo to the south. In between the two bustling cities is Collins' adopted hometown of La Manzanilla, an idyllic, dusty fishing village of 3,000 (give or take a few wayward tourists during high season). Among the residents are many American and Canadian expats who find the leisurely way of life in "real Mexico" to their liking.

Yet it's fair to say that Collins, who now has dual citizenship, is not living in La Manzanilla for the margaritas and natural rays of vitamin D. The former humanities professor and passionately eco-minded son of two Peace Corps workers in Africa, founded Tierralegre (Happy Land), a group that protects the natural resources and biodiversity of this region best known for its surrounding estuary. The coast here is marked by a series of bio-diverse mangroves, critical in protecting the coastline and providing refuge for dozens of endemic species, including the largest population of American crocodiles outside the United States.

Collins, a professional whitewater kayaker and former nature consultant for the Discovery Channel, settled here in 1999, guiding paddle trips through the brackish waterways buzzed by mosquitos and shadowed by dense, prehistoric-like red mangrove trees.

Collins knew the disheartening statistics — Mexico has already destroyed 75 percent of its existing mangroves — and he was determined to raise the red flag of awareness.

"Mangroves are critical throughout the world in terms of providing breeding grounds, filtration of water, slowing costal erosion and providing a natural habitat," he said, talking while paddling a few curious visitors quietly through his magical world.

La Manzanilla's mangrove is now on the Ramsar List of Wetlands of International Importance, a critical step in keeping development at bay.

With that tenuous victory stowed away, Collins began to focus on another issue that burned deep in his lungs. Troubled by the common local practice of burning trash, particularly plastic, Collins kick-started La Manzanilla's first-ever, organized recycling program in 2005. He knew the locals needed to be persuaded to stop burning garbage and to understand the benefits of recycling — but he also knew that "being a gringo on a pulpit is not effective."

So he made connections in the conservation network and invited a professor from the University of Guadalajara to address the natives of La Manzanilla, whose staggering use and disposal of plastics threatened the bay and surrounding habitat.

"We just planted a seed of consciousness," said Collins. "And we realized there was a demand for plastics," with entrepreneurs hauling it away and reaping 1 peso (about 80 cents per kilo).

In 2007 he founded Tierralegre. Part of that group's effort involves supporting the La Gloria Sea Turtle Rescue Program, an off-the-grid, beachfront research station that protects four of the world's seven sea turtle species. Tierralegre's newest project involves a plan to counteract deforestation in the area by planting bamboo, a fast-growing, sustainable tree with a variety of uses, including as a building material. Using grant money from Comisión Nacional Forestal, Mexico's National Forestry Commission, the project stands as a crucial step toward local sustainability.

Collins' leadership and community involvement have been contagious, with La Manzanilla's strong expat contingent pitching in to make their homes away from home more livable. They patrol beaches to help protect turtle eggs, they help build and paint recycling containers, they volunteer at Cisco's Amigos, an annual five-day spay and neuter clinic, they donate supplies to the village's only medical clinic run by a female M.D. from Guadalajara, or they teach English to locals at either the used bookstore or the La Catalina Language School.

Expats have built a new nonprofit multicultural center where locals and visitors take classes in pottery, painting, language, dance, yoga. Fulltime resident Eileen Zack teaches hands-on cooking classes with an international bent, and a high-end gallery shows custom-made jewelry and folk art.

Many of these north-of-the-border transplants own homes and businesses here. A former Silicon Valley software engineer named Willy runs Palapa Joe's (www.palapajoes.net), an American-styled restaurant/cantina on the town's only paved street a block up from the shore of gentle-waved Tenacatita Bay.

Willy lives the good life, playing music with his band The Lounge Lizards, tending bar, holding court with fellow expats, watching American sports on satellite TV.

They hear the horrorific accounts of warring drug cartels in Mexican border states, but that seems a world away, and their struggles run more along the lines of updating a sewage system in gross disrepair, preventing a wayward crocodile from snacking on local dogs, or collecting volunteers for the community garden.

An annual visitor to Palapa Joe's is none other than Food Network chef and television personality Guy Fieri, whose parents have visited La Manzanilla for years. In January, Fieri took over the restaurant's kitchen for the third year in a row, cooking for dozens of locals, expats and tourists to raise money for the kitchen at the local kindergarten, so all the children are guaranteed at least one nutritious meal a day.

Fieri's visits to La Manzanilla produce stories about the gregarious Food Network star. One year he took over a hot dog cart for a few hours in the town square, cooking up a now-famous Fieri Mexican mélange, and he's been known to tilt a few shotglasses around town.

Despite that big-name connection, La Manzanilla goes largely unnoticed by the rest of the world. One can walk the three-mile stretch of beach from the rocky shores south of town to the eco-resort of Boca de Iguanas to the north and not pass another soul.

La Manzanilla embraces this sleepy image. The town has no stoplights, no banks, no ATMs and just one often-closed internet café. Local tiendas offer fresh fruit and vegetables and other food items, two local women run a tortillaria, nightly taco stands sell plates of tasty, authentic food for around a buck, and a fish cooperative gives locals and visitors access to fresh-caught seafood. The town is a tropical paradise blending old world charm with enough modern conveniences to lend an ease of living.

The tourists who do visit can rent beachfront condos with apt names such as Tranquilidad (tranquilidad-rentals.com) and Alegre Mar (www.alegremar.com) for under $100 per day in low season. Visitors spend most days in languid repose, soaking up equal doses of sun rays and culture. The only tourist highlight, if you can call it that, is taking one of Collins' boat tours through the mangrove, as he expertly narrates the sights and sounds of this natural wonderland, where crocs rule the brackish depths and, above, white ibis, snowy egrets, wood storks, roseate spoonbills, ringed kingfishers and the aptly named magnificent frigate bird (Collins has counted 60 species) soar and swoop and roost in what is, so far, an acknowledged sanctuary.

Loving and protecting this happy coast and its simple way of life is a daunting task filled with heartbreak. Collins packed his bags once, leaving this beautifully fragile place without its most ardent defender — and leaving a gaping hole in his life.

"I had to come back," he said. "It seems we need each other."

• • •

If you go

Getting there: Airports include Manzanillo (an hour south of La Manzanilla, or Puerto Vallarta, three hours north.

Lodging: La Manzanilla has a large number of vacation rentals. See www.visitlamanzanilla.com, www.lamanzanilla.info or www.santanarentals.com.

Dining: La Manzanilla has only 3,000 residents but boasts nearly 40 restaurants during high season. Street vendors and taco stands are also very popular with locals and tourists.

Conveniences: There are no banks or ATMs in town, and credit cards are not accepted. Wireless internet is available from many restaruants and rentals. |

|

|  |