|

|

|

Editorials | Issues | May 2007 Editorials | Issues | May 2007

Questions Linger About Mexico's 'House of Death'

Dave Montgomery - McClatchy Newspapers Dave Montgomery - McClatchy Newspapers

| | The House of Death in Ciudad Júarez, Mexico (Klaas Wollstein/Narco News) |

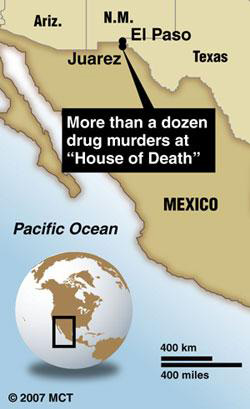

The code phrase was "carne asada": a barbecue. When word went out that one was going to be held at the two-story residence in Juarez, Mexico, just across the border from El Paso, Texas, it meant that one of Mexico's powerful drug cartels planned to kill a perceived double-crosser or a rival operative.

The U.S. government had an informant in the House of Death on Parsioneros Street, where at least a dozen people were tortured, executed and buried. The informant, Guillermo Eduardo Ramirez-Peyro, witnessed or knew in advance of several of the executions, and federal law-enforcement officials paid him $224,650 for four years of undercover work. His handlers in U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement continued to use him even after they found out that he'd witnessed a murder in August 2003.

Ramirez was a mole for ICE while he was a lieutenant to Heriberto Santillan-Tabares - also known as "El Ingeniero," the engineer - a chieftain in the Juarez-based cartel who allegedly ordered the killings. Immigration transcripts, depositions and ICE documents describe Ramirez's double life, providing chilling details of the carnage as well an insider's account of the violent Mexican drug trade.

"Santillan spoke with me that he was going to `grill some more meat'; in other words, they were going to kill some people," Ramirez said in recalling one execution.

The former high-ranking figure in the cartel headed by Vicente Carrillo Fuentes Ramirez has acknowledged that he witnessed two executions, one of which he recorded, either with his cell phone or a video recorder. He also said he'd bought duct tape and lime to dispose of bodies, supervised burials and arranged the use of the house for a "carne asada." On one busy day, hit men took a body to the house, threw it under the staircase and returned about 45 minutes later with another body wrapped in black plastic. They dumped that one in the kitchen.

The informant Ramirez also tells of hit squads composed of corrupt Mexican police officers and high-ranking law enforcement officers enmeshed in the drug trade.

He remains in protective custody in the United States, fighting U.S. government attempts to deport him. Being sent back to Mexico, he asserts, would mean death at the hands of the drug lords he betrayed.

The House of Death story has received limited public attention - the most extensive reports have been in the online publication Narco News - since it began unfolding in early 2004. The House of Death story has received limited public attention - the most extensive reports have been in the online publication Narco News - since it began unfolding in early 2004.

The families of six of the victims have lodged a wrongful-death suit against the U.S. government, alleging that ICE officials monitored the killing or that federal prosecutors and ICE agents were aware that their informant was participating in subsequent killings and kidnappings. Justice Department policy prohibits confidential informants from participating in acts of violence. The suit is pending in federal court in El Paso.

The findings of an internal U.S. inquiry that included interviews with more than 40 agents and others haven't been released. Along with ICE, which is now a branch of the Department of Homeland Security, and the Justice Department, the Drug Enforcement Administration was part of the multi-agency task force that was investigating the Juarez cartel.

Accusations also have been aimed at the office of U.S. Attorney Johnny Sutton of San Antonio, who's also come under fire for prosecuting two Border Patrol agents in the shooting of a drug courier and a south Texas sheriff's deputy for firing on a carload of immigrants.

Sandalio Gonzalez of Miami, a now-retired DEA supervisor who wants Congress to investigate the case, has accused Sutton of retaliating against him after Gonzalez wrote a fiery letter to his ICE counterpart in February 2004. A copy of the letter was hand-delivered to the U.S. attorney's El Paso office.

Gonzalez, who was then the DEA's special agent in charge in El Paso, accused ICE of mishandling the investigation, going to "extreme lengths" to protect a "homicidal maniac" informant, endangering the lives of DEA agents and allowing subsequent murders by continuing to use Ramirez.

The letter caused an uproar that reached all the way to Washington. E-mails produced in a whistle-blower retaliation case that Gonzalez filed indicated that Sutton had called Justice Department officials in Washington expressing concern about "a rather lengthy and inflammatory letter" from the DEA supervisor.

"Johnny was not sure who was talking, but we are certainly concerned that there may be press, and there may be inquiries here in DC as well," Associate Deputy Attorney General Catherine O'Neil said in a March 4, 2004, e-mail to other Justice Department officials and DEA Administrator Karen Tandy.

On the subject line, she wrote: "Possible press involving the DEA Juarez/ICE informant issue."

"DEA HQ officials were not aware of our el paso (sic) SAC's inexcusable letter until last evening ...," Tandy said in an e-mail the next day. "I apologized to Johnny Sutton last night and he and I agreed on a `no comment' to the press."

Gonzalez, in his whistle-blower petition, said the DEA's chief of operations had called to admonish him and had said, "Mr. Sutton was very upset," because his letter could provide evidence that would hurt the government's case against Santillan.

The DEA subsequently downgraded his performance review because of Sutton's "retaliatory" actions, Gonzalez charged. The agent and the DEA later settled the claim "to my satisfaction" in a confidential agreement, Gonzalez said in a telephone interview.

DEA officials have said that Gonzalez improperly went outside channels in sending the letter and should have discussed his concerns with superiors first.

Shana Jones, Sutton's spokeswoman, said the pending wrongful-death lawsuit, which is heavily based on Gonzalez's accounts, prevented the U.S. attorney from commenting.

Officials for ICE and the DEA have declined comment for the same reason.

The Justice Department acknowledges that Ramirez was a government informant who was "present at a murder in August of 2003." But it denies the lawsuit's assertions that he participated in subsequent killings.

Ramirez, under questioning in his immigration hearing, has testified that ICE agents had advance knowledge about murders.

Ramirez was a Mexican highway police officer when he opted for a career change in the mid-1990s, serving as a distribution manager in the Mexican drug network before becoming Santillan's second in command.

He became a U.S. operative after he walked across an international bridge in 2000 and made contact with a U.S. Customs officer. Ramirez said he "didn't like the way" the cartel operated and felt it would "be honorable" to work for U.S. law enforcement.

Ramirez went by the nickname "Lalo" and also used the alias "Jesus Contreras." His handlers, in their investigative reports, referred to him by his code name: SA-913-EP. He claims that the U.S. government owes him another $400,000, "more or less."

Santillan was sentenced to 25 years in prison in 2005 after he pleaded guilty to conducting a criminal enterprise. Other charges against him were dismissed as part of a plea agreement.

The independent Narco News Bulletin has been following and documenting this story for over two years. Journalist Bill Conroy has published over forty articles which lay out a horrific story of torture, corruption, murder - and a US Dept. of Justice which not only condones it, but is involved. Read about it at NarcoNews.com/HouseOfDeath |

| |

|