|

|

|

Editorials | Issues | July 2007 Editorials | Issues | July 2007

Argentina's "Dirty War" Trials Continue, Families Testify

Sam Ferguson - t r u t h o u t Sam Ferguson - t r u t h o u t

go to original

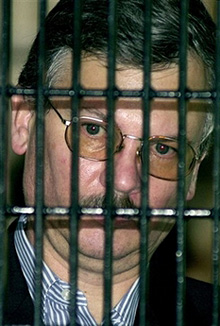

| | Ricardo Miguel Cavallo of Argentina, a former military officer, is seen in this Aug. 26, 2000 file photo in a Mexico City jail. Spain's Supreme Court ruled Wednesday that the key Argentine dirty war suspect who is in custody in Spain will stand trial in Madrid, rejecting a lower court ruling that he should face justice in his own country. Ricaro Miguel Cavallo, a former military officer considered a major figure in the repressive, violent military juntas that ruled Argentina in the 1970s and 1980s, was extradited from Mexico City to Madrid in 2003 after Spanish Judge Baltasar Garzon charged him with genocide, terrorism and other crimes.Cavallo was a navy commander in Buenos Aires and worked in the Navy Mechanical School, known by its Spanish initials ESMA, which became a notorious detention center in Buenos Aires where thousands of prisoners were tortured or executed. There were very few survivors. (AP/Victor R. Caivano) |

La Plata, Buenos Aires Province, Argentina - Three members of the Miralles family, all disappeared by Argentina's military government in 1977, testified Thursday in the trial of Father Christian Von Wernich, indicted for crimes against humanity. They testified about physical and psychological torture at the hands of the Argentine police, a priest and a medical doctor.

Carlos and Julio Miralles are alleged to have been kidnapped and used by the police as bait for their father, Ramón Miralles. Both Carlos and Julio related an incident in which Father Von Wernich encouraged them, after being tortured, to confess "for god and country." It was the second day of testimony before the three-judge tribunal that will ultimately decide the case, expected to last until mid-September.

Father Von Wernich, 69, served as chaplain to the Buenos Aires police force during Argentina's "Dirty War." From 1976-1983, the military government kidnapped and illegally detained as many as 30,000 people. The whereabouts of many of the desaparecidos - the "disappeared" - are unknown to this day, though they are presumed to have been executed by the government at one of the clandestine detention centers then maintained throughout Argentina. Father Von Wernich is being charged as an accomplice on seven counts of murder, 30 counts of torture and 41 counts of deprivation of liberty for his role in the state repression of the disappeared at several detention centers within Buenos Aires province. Von Wernich had been shielded from prosecution by amnesty laws passed shortly after the collapse of the dictatorship. However, the amnesty laws were declared unconstitutional by the Argentine Supreme Court in 2005. As a result, over 1,000 crimes from more than twenty-five years ago are now under investigation.

The first witness of the day, Julio Miralles, was noticeably disturbed as he took the stand. Previously, Julio Lopez, a key witness in a recent case against former Buenos Aires Police Chief Miguel Etchecolatz, was disappeared 10 months ago, after testifying in the case. Though the circumstances of his disappearance remain unsolved, most suspect it was an effort to chill future testimony. Lopez had received threatening phone calls for several days prior to his testimony.

Thursday, Julio Miralles, hands shaking, told the court, "I'm terrified to be here." His mother had also been disappeared for two days, after the democratic transition, when his family filed a lawsuit against Ramon Camps, the police chief responsible for their disappearance.

According to Carlos and Julio, on May 31, 1977 several plainclothed men, claiming to be police officers, came to the Miralles family home looking for Ramón Miralles, the former Buenos Aires economic minister. Ramón, however, was away on vacation with his wife. The police pushed their way in and ransacked the house. They asked Julio, Carlos and Luisa Villar, Carlos's then-pregnant wife, to come with them. The three were blindfolded and put into two separate cars, Julio and Carlos in one, Villar in the other. They spent several days at a police station, and were then transferred to Coti Martinez, a clandestine detention center in Buenos Aires province.

Julio referred to the detention center as "a terrifying place." He gave a first-person account of torture techniques used on him: "I was stripped naked, soaked, and shocked all over the body - my head, my genitals, everywhere - as they interrogated me." The line of questioning centered around his father: "Where was he? What were his activities?" Some time later, General Carlos Suárez Mason, one of Argentina's most notorious repressors, appeared "with a surprise. He told us he had somebody we loved dearly." It was his father Ramón.

Ramón Miralles, 85, was expected to testify Thursday, but was excused for medical reasons. However, in Nunca Mas, the official government report on the disappeared authored in 1984, just a year after the return of democracy, Ramón related that his family was being held hostage "to force me into giving myself up." Ramón was kidnapped by the police after he filed a habeas action on behalf of his family.

Both Julio and Carlos testified that they saw Father Von Wernich on several occasions while detained at Coti Martinez. During one incident, Von Wernich allegedly encouraged them to "confess, so that you are not treated like this anymore, not tortured. It is for the good of God and country."

"He tortured us with his talks," Julio related. "Do you know what it is like, in these moments of terror, of torture, to see a representative from the church? It was as if God came to give us a hand, but, in fact, it was the devil." Julio told the court that information discussed with Father Von Wernich, ostensibly between the two of them, was later revealed to him in torture sessions. That directly contradicts Von Wernich's anticipated "religious privilege" defense. Lawyers for Von Wernich have defended his actions by claiming that the priest was there in a religious capacity to hear confession. According to the defense, information revealed to a priest in confession must be guarded by the priest and cannot be shared, even with a criminal court.

Carlos, and his then-wife Luisa Villar were freed after nearly a month. Julio and Ramon were then transferred to Puesto Vasco, another detention center in Buenos Aires province, where Julio also claims to have seen Von Wernich on two occasions. Previous witnesses corroborated this encounter.

Thursday's revelations, however, may be more damaging to Father Von Wernich, as all of the witnesses so far have described Puesto Vasco as a less-hostile place than Coti Martinez. While still tortured at Puesto Vasco, victims were often moved to different locations, suggesting that Von Wernich may not have been aware of the torture. The Miralles family testimony, however, places the priest inside of a brutal detention center, where he could "easily see the marks of torture," according to Carlos.

Villar, the third witness of the day, never directly saw Father Von Wernich. She only heard from other detainees that they had interactions with a priest.

The tribunal's line of questioning, however, was not limited to Father Von Wernich. Under Argentine law, facts revealed in the course of one trial may be used in future criminal cases. As several investigations are ongoing against other interrogators from the detention centers, the tribunal and lawyers for the victims questioned the witnesses about other incidents in Coti Martinez and Puesto Vasco.

The tribunal focused on Villar's interactions with Doctor Berges. Berges was the medical supervisor within the detention centers. His role was to determine whether or not victims could withstand further torture. He was convicted of crimes against humanity in 1986, but was later pardoned by President Menem. Villar, who suffered a miscarriage in Coti Martinez, was denied medical attention, though she requested it.

Carlos, who testified just before Villar, told the tribunal that "out of all of us, [Villar] suffered the worst treatment. There are things that happened to her when she was alone that she keeps inside."

The tribunal asked Villar directly about her treatment. She told them that she was taken off by herself when tortured. She limited her response, however, to simply commenting, "we were all tortured in our own way, some of us physically, some of us psychologically, some of us morally." When the tribunal asked her to expand on her treatment, she paused, contemplated her response, but, on the verge of tears, refused to expand. "I was tortured."

Sam Ferguson is a JD candidate at Yale Law School and a former Senior Researcher at the Rockridge Institue under George Lakoff. He is investigating the problems of transitional justice and democratic consolidation after periods of military rule. He is currently living in Buenos Aires. |

| |

|