|  |  |  Health & Beauty | September 2008 Health & Beauty | September 2008

The Battle Over Childhood Obesity

Keith Darcι - San Diego Union-Tribune Keith Darcι - San Diego Union-Tribune

go to original

|

|

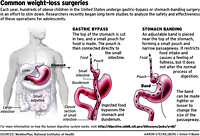

Click image to enlarge | | Gastric bypass and stomach banding typically cost half as much in Mexico as they do in the US. | | |

Tijuana Tipping the scales at just under 300 pounds, 13-year-old Joey Fishell of San Diego agreed to travel to Tijuana with his mother.

Instead of landing on Avenida Revolucion like most tourists do, they made a bee line for one of the city's weight-loss-surgery clinics.

Other obese children from the United States and their parents are taking the same path.

The operations typically cost half as much in Mexico as they do in the United States, a crucial difference when insurance companies deny coverage. Also, doctors in Tijuana often are willing to take patients who don't meet the criteria employed by most American weight-loss surgeons.

In Tijuana, Hospital Angeles and at least four smaller specialty clinics market themselves, primarily through Web sites, to people seeking the two most common procedures gastric bypass and stomach banding.

Joey said he thought his mother, Dante Fishell, was "crazy" when she suggested that the two of them have weight-loss surgery together in Mexico.

To persuade her son, Fishell said she focused on good things that would come from the operation, such as Joey being able to skate faster when practicing with his ice hockey team and having more energy during the school day.

She also warned him that obesity would cut short his life.

"I think in 10 or 15 years without the surgery, there wouldn't be a life," Fishell said in a recent interview. "I'm just afraid that his heart won't make it if he keeps putting on this weight."

Since his July 2 surgery, Joey has lost 59 pounds and has started the new school year as an eighth-grader. He and his parents said they're happy with the outcome so far.

But undergoing weight-loss surgery in another country can be risky, especially for children, several U.S. physicians and health officials said. They stressed the importance of pre-screening and post-surgical care.

Among their concerns:

Surgeons in other countries may not thoroughly screen their overseas clients to determine whether they're suitable candidates for weight-loss procedures.

Medical complications can surface days after the patients return home, leaving them in the lurch to find a nearby surgeon willing to take on their case.

In the long run, patients lacking follow-up care can suffer malnutrition or eat too much and regain the pounds they lost.

Doctors at the University of California San Diego Medical Center in Hillcrest and La Jolla are seeing a growing number of people who need care for complications from weight-loss surgeries performed in Mexico, said Dr. Santiago Horgan, the hospital's director of minimally invasive surgery.

"The key to the success is the after-care," he said. "Patients need to understand that when you go out of the country, you get what you pay for."

Even under the best conditions, providing long-term follow-up care to young weight-loss patients can be difficult, said Dr. Kelvin Higa, a professor of surgery at the UC San Francisco Medical Center and former president of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

The busy lives of teenagers can leave little room for trips across town to the doctor's office, much less to one in another country. Things only get more complicated when young patients move away from home, head to college or start a full-time job as they transition to adulthood, Higa said.

U.S. physicians usually require monthly checkups for at least a year after surgery to monitor weight loss and nutrition issues.

In the case of stomach banding, they prefer to tighten the implanted ring gradually so less and less food enters the stomach. Tightening the band too much could block food from moving through the stomach and cause patients to regurgitate. If the band is left too loose, the patients might eat too much and regain weight.

So the doctors make as many as six adjustments called "fills" during the first year after surgery.

In Tijuana, weight-loss surgeons favor far fewer adjustments.

Dr. Ariel Ortiz of the Obesity Control Center tells his male patients to come back to his clinic about six weeks after stomach banding for a single fill. Women receive as few as three fills.

Ortiz applies his standards to patients of all ages and said he hasn't encountered any serious problems after performing stomach-banding surgeries on more than 6,000 patients in the past 11 years.

He said his center, located about 10 blocks from the San Ysidro border crossing, is one of the busiest stomach-banding clinics in the world.

On the day of surgery, Ortiz gently lectures patients on their post-surgical responsibilities: They must eat a third less food, consume meals more slowly, eat healthier meals and exercise regularly.

"You're not home free. You're on the home stretch," he told a stomach-band patient just before she was wheeled into the operating room on a recent day.

For three weeks after surgery, patients must consume only liquids because solid food can dislodge the band. From then on, they must chew food into pieces small enough to slide through the restricted opening created by the band.

Equally important are comprehensive pre-surgery screenings designed to gauge whether a person should have a weight-loss operation, said some bariatric specialists in the United States.

Gastric bypass and stomach banding should be considered only after a youngster has failed a six-month, physician-monitored weight-loss program, according to guidelines set by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Also, a thorough psychological evaluation should be conducted to determine whether a potential patient has mental dysfunctions, such as depression or drug abuse, that could block weight loss. The exam also is meant to see if a person possesses the coping skills needed to succeed after surgery, such as the ability to replace food addictions with healthy behaviors.

Failing to identify and address underlying mental and emotional issues before surgery could lead to significant problems after the operation, said Dr. Edward Mason, a professor emeritus of general surgery at the University of Iowa and the man who pioneered weight-loss surgery in 1966.

"It's possible that they will be very disturbed by taking away their ability to overeat," he said.

There has been no large-scale analysis of how children fare psychologically after weight-loss surgery. But a study by researchers at the University of Utah, the University of North Carolina and the University at Buffalo found that the suicide rate among adult patients was more than double that of obese adults who didn't have the surgeries.

The study, featured in the New England Journal of Medicine last summer, tracked nearly 10,000 people in Utah who had undergone gastric-bypass surgery between 1984 and 2002.

In Tijuana, the comprehensive pre-surgery screenings almost never occur.

For example, Ortiz meets most of his clients for the first time when they arrive at his clinic. Mental evaluations are done during casual conversations.

Ortiz said he has never rejected an adolescent patient for psychological reasons.

"What we are looking for in teenagers is a certain maturity level, that they understand what procedure they are undergoing," he said. "Usually they are a lot more mature for their age, most probably because of the things they have to undergo as obese teenagers."

Ortiz didn't ask Joey Fishell many questions before performing the surgery on July 2. The boy was accompanied by his mother, who also would undergo stomach banding that day.

Fishell and her husband, Mike, sought out Ortiz after learning that their health insurer doesn't cover stomach banding. The couple had decided against a gastric bypass because they believe it's a riskier surgery.

Money also played a role in the Fishells' decision.

Ortiz's charge for stomach banding around $8,000 was less than half the amount that doctors in San Diego quoted for the operation, Mike Fishell said.

At 13, Joey had started to recognize the damaging effects of obesity on his health. Blood tests indicated that his glucose levels were nearly high enough to trigger type 2, adult-onset diabetes, a condition that has risen among children along with the nation's increase in childhood obesity.

Joey was familiar with the disease because the inherited version, known as type 1 diabetes, runs through his mother's family. Dante Fishell, 39, developed diabetes as a teenager and takes insulin every day to control it. Her mother died from complications related to diabetes two years ago at 61. Joey's aunt and a few cousins also are diabetic.

"I worry about becoming diabetic every day," Joey said shortly before traveling to Tijuana for his surgery.

He can't remember a time when he wasn't overweight.

Photographs in his family's Clairemont home chronicle his weight gain from his earliest years. In one studio portrait taken when he was 3, Joey's plump arms bulge out of the sleeves of his T-shirt.

The bullying started as soon as he entered kindergarten.

"I would be called fat. My mom would walk me to school every day, and they would ask her why her son was so fat. And she would break down," Joey recalled. "I wouldn't talk. I was very quiet, and I still am to this day."

As the taunting intensified in middle school, his anger boiled over into fistfights with schoolmates. In early 2007, halfway through Joey's seventh-grade year, his parents allowed him to transfer to another school.

Joey's first semester at his new school in the spring was largely peaceful, he said, and he made some friends.

"I told them that I'm going to be changing how I look," he said. "Some of them didn't really think it would happen. So I told them, 'Next year, I'll be different.'"

Six weeks after his surgery, Joey returned to Ortiz's clinic to have his band tightened. Accompanying him were his father and an aunt, who both underwent the stomach-banding procedure that day.

Joey's shirt size has dropped from XXX-large to extra-large, and his 52-inch waist has shrunk to 44 inches. He has added hockey pants to his Christmas wish list because his old pair won't stay up without suspenders.

When Joey started eighth grade at Standley Middle School late last month, staff members and other students had a hard time believing their eyes.

"I walked into (the school) office, and no one thought it was me," he said. |

|

|  |