|

|

|

Travel & Outdoors | Destinations | January 2005 Travel & Outdoors | Destinations | January 2005

The Quest: Take the Last Great Safari

A Land Rover, a guide, and 5,700 square miles of untouched Serengeti: Finding a few million animals shouldn't be that hard, should it? A Land Rover, a guide, and 5,700 square miles of untouched Serengeti: Finding a few million animals shouldn't be that hard, should it?

Driving down the slope of the Ngorongoro volcanic crater onto the floor of one of Africa's great game reserves, my guide, Anthony, eagerly points out the animals: Here a ringed plover flits on a fever tree; there a warthog kneels in the long grass, snorting as a gathering of old and ornery buffalo gaze at our Land Rover. "It is like a very big zoo," Anthony says, "but here the animals eat each other." Driving down the slope of the Ngorongoro volcanic crater onto the floor of one of Africa's great game reserves, my guide, Anthony, eagerly points out the animals: Here a ringed plover flits on a fever tree; there a warthog kneels in the long grass, snorting as a gathering of old and ornery buffalo gaze at our Land Rover. "It is like a very big zoo," Anthony says, "but here the animals eat each other."

In Africa the big bucks in the safari business are in the big-name big game, and Anthony races around Ngorongoro trying to show me all the slide-show species. I have come with another aim in mind, I say. My prey is the skinny, bearded, long-faced, grass-grazing beast called the wildebeest. Also known as the gnu-from the sound of its grunt-the wildebeest is the plainest of the plains and an unlikely attraction for a safarigoing tourist. Anthony turns across the salt flat toward a small group of wildebeests. I tell him I am not after just a few gnu: I have come in search of the last great migration on earth. Every year a group of some 1.5 million wildebeests range over the wilds of East Africa, from the Grumeti River to the grasses of the Serengeti. Anthony nods. "Tomorrow we will find the wildebeests," he says.

That night, I read that these wildebeests have followed the same oddly shaped clockwise route forever, in rough outline, but because of the varying weather the location of the herds can't be predicted, even by the Masai natives. Each day, when the sun sets, the wildebeests watch the sky, always moving toward the rain and the next day's water. Even though the migration can be enormous, it can move up to thirty-five miles a day in any direction, and tracking it can be extremely difficult.

The next morning, I rise with the sun, the peak of Kilimanjaro covered in clouds on the horizon. We set out for the plains of the Serengeti. Masai boys stand by the side of the dirt road dressed in blood red robes, faces painted white, dancing a jig, hoping we'll stop and pay to have a photo taken. They are teenagers, Anthony tells me, and they have just been circumcised. After they become warriors, he says, they must go out and kill a lion with a spear. The next morning, I rise with the sun, the peak of Kilimanjaro covered in clouds on the horizon. We set out for the plains of the Serengeti. Masai boys stand by the side of the dirt road dressed in blood red robes, faces painted white, dancing a jig, hoping we'll stop and pay to have a photo taken. They are teenagers, Anthony tells me, and they have just been circumcised. After they become warriors, he says, they must go out and kill a lion with a spear.

"They dance like they're still in pain," I say. "It hurts so very much," he says.

We drive for hours, but there are no gnu signs. By late afternoon, the guard at a gate to Serengeti National Park can only report that they were last spotted at the Gol Mountains a week ago.

The Serengeti is an ocean of grass. There are no fences, no signs of man, nothing but a vast treeless prairie of incredible beauty. The time is growing late-and we have to be out of the park by last light. We turn off the main dirt road onto a muddy track and bounce along for another hour. There are eagles and Thomson's gazelles and a jackal gnawing the knee bone of a zebra, but no wildebeests.

The sun is now beginning to set. The grass is shorter here, the water holes are full-hopeful signs, Anthony says. But we haven't come across dung for miles, and there are no hoofprints to follow. Failure is a real possibility: A million animals are a needle in this 5,700 square-mile haystack.

"Are we going to find them, Anthony?" I ask. He doesn't speak. He slowly surveys the savanna. This is the moment when the safari turns to something more serious. We will do this, his manner says. It is now our mission - my quest, his pride-to find the beasts. "My real name-my African name-is not Anthony," he says. "It is Nyambacha." Nyambacha hands me his binoculars. "We will find the herd now," he says.

We turn off the mud track altogether. There is no path now, just virgin plain, and Nyambacha veers wildly to avoid termite hills and hares poking out from the ground. Gazelles run alongside the truck like dolphins next to a ship. Dung beetles begin to bounce off the windshield and my face. We come across a huge gathering of wildebeests, maybe 100,000, and I think we have found our prey, but Nyambacha says there are many more than this: These are the outriders of the herd. Nyambacha races farther into the wild, now going better than seventy, when suddenly he locks the brakes, and we slide to a stop in a dust cloud. "In the distance," Nyambacha says.

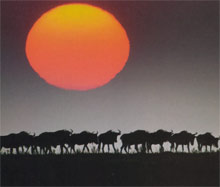

And there they are. The wildebeests of the Serengeti stretch farther than the eye can see. Ten miles long and one mile wide, the migration covers an area nearly the size of Manhattan. It is more than a herd. It is an army. A nation. "I have never seen so many," Nyambacha says.

The wildebeests are spread out and grazing. They are still and unguarded, and the scene is seemingly undramatic. They are uglier than I expected, hammerheaded and skinny and gnarly. But when I get out of the Land Rover and stand on the Serengeti under the darkening sky, a huge and indescribable feeling of joy fills me. The male wildebeests grunt and piss and shit and lay claim to their temporary piece of territory. There is no other human being for miles and miles in any direction.

It is only as the wildebeests slowly start to amble south, toward distant thunderheads, that I realize they have silently, instinctively, moved as far away from me as possible.

-Guy Lawson |

| |

|