Cuba's Historic Baracoa

Scott Messenger - The Journal Scott Messenger - The Journal

The short road from Santiago de Cuba to Baracoa might, in fact, be slowest in the country. After meandering through shoulder-high sugarcane and up into rolling foothills, the La Farola highway cuts through verdant mountains, where it runs steep and narrow, making each bend a blind corner. This is a second-gear road at best.

Not that there's any hurry. For one thing, this is Cuba, and no one's in a hurry; for another, if the sun hasn't reached its zenith, the morning blanket of mist remains, and, below, the eastern coastal province of Guantanamo is a landscape in silhouette.

For the past several days, I have been keeping a brisk pace, trying to see too much in too little time. I'd heard Baracoa, while out of the way, would be a good spot to overnight before the trip back to Havana. But no one, I discover upon arrival, just overnights in Baracoa. If you haven't booked departure before you even arrive, expect delays.

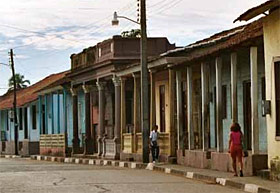

After walking the Malecon, an avenue along the Atlantic, or meandering the colonial neighbourhoods, or relaxing in a cafe off lively Parque Central, you start to feel the gravity of the place, welcoming and irresistible.

It's hard to believe that Baracoa, a town about as far from Havana as you can get, figures so prominently in Cuban history.

It was here that Columbus spent a week, just after arriving in 1492. In 1511, Diego Velazquez returned here, establishing the island's first Spanish colony, and embarked upon a campaign of brutality that would all but eradicate the indigenous population.

Surprisingly, the town makes relatively little of this historical significance. At the north end of Malecon is a statue of Hatuey, burned at the stake in 1512 for leading the resistance against the Spanish.

Head into the town centre to the crumbling Cathedral de Nuestra Senora de la Asuncion in Parque Central and find inside the Cruz de la Parra, a wooden cross said to date to Columbus. The explorer himself now watches over the Spanish fort of Matachin at the southern terminus of Malecon. The fort houses an interesting, cursory historical exhibit.

For details, see the gardener. Noticing me enter the fort, he sets down his scythe and leads me to the armoury to see ancient cannons and swords. Then, in graciously slow Spanish, he explains how soldiers would man the walls with muskets and describes the assaults they endured over the centuries. He also shows me a hidden plot where growing his own lunchtime vegetables has been prohibited. Sighing, he tells me that once as a younger man he'd played saxophone in a band. Not anymore, he says, tapping a sculpted shoulder. Too sore. Too tired.

I had seen El Yunque, or The Anvil, a mountain that looms remote and ominous beyond the wide, placid Bay of Baracoa. Anna and Armando -- the elderly couple run one of Baracoa's Casas Particulares, or Cuban B&Bs -- assure me it can be climbed.

In between making chamomile tea, introducing me to friends, sharing Baracoan chocolate, showing family photos and frying marlin for dinner -- Anna and Armando explain how to pass the Baracoan day. They suggest the flat-topped mountain.

The hike organized by an agency in town begins with a rough drive over rural roads. A stroll through a cocoa plantation allows our group, Europeans and a few other Canadians, to get acquainted.

Minutes later, we reach the Rio Duaba and watch our guide, a 20-something Cuban ironman, plunge into the water. The nature walk, we realize, is over.

After battling swift current and slick stone, we gain the shore, weak-kneed and winded, only to find a relentlessly uphill ribbon of thick, red mud.

For the next 2 1/2 hours, we trudge in silence, exhausted by humidity and exertion, groping our way by trunk and branch, leaping puddles and sharp stones.

Reaching the summit, we are rewarded with views of the vast Atlantic and the hazy outline of Haiti. Relief is short-lived. Before our breathing returns to normal, Cuban ironman is ready to head back. Tonight, like every night, he is hitting the disco in Baracoa. He needs the later afternoon, apparently, to rest.

Too tired and self-conscious for the disco that night, I visit Casa de la Trova beside the decaying cathedral, where a band plays the songs Ry Cooder revealed to North America. While the locals dance and the tourists drink, I catch myself nodding with fatigue. Reluctantly, I slip back to my casa.

Parque Nacional de Alejandro de Humboldt, 45 minutes from Baracoa, allows a more leisurely pace. A Unesco world heritage site since 2001, the area is home to the richest biodiversity in the Caribbean.

The guided tour makes lots of stops for gawking at birds, frogs, lizards, plants, bugs, views and, happily, for snacking. Ironman, our guide once again, plies us with fresh guava, tiny pineapples, bittersweet cocoa and rich coconut milk.

It was our last stop, however, that is perhaps the most memorable. Though there is more than one waterfall in the park, the one on the Rio Santa Maria is unique, featuring a deep, blue pool. Ironman suddenly strips to his Speedos, steps casually off a rocky ledge and makes a perfect dive.

The sky clouds over and we leave the park for a quick swim at Maguana Beach, but the white sand beach seems desolate and the ocean uninviting. So we crowd around the snack bar for buck-a-bottle beer, and watch a local man tinker with the stubborn engine of the antique motorcycle he'd just ridden in on.

When we get back to Baracoa, it is late afternoon. Children are running home from school, the scarves of their uniforms unknotted and fluttering like kite-tails. On sidewalks, men are settling into games of cards and dominoes. And back at my casa, Anna and Armando are waiting with dinner.

That night, I return to Casa de la Trova. There was a new band on stage: aged grandfathers in sunglasses and leather jackets. It might have been incongruous had the music not possessed such vitality.

Again, the locals danced and the tourists drank. Besides the ones I know, the band also plays songs missing from Cooder's collection. More songs about love and Cuba and Che Guevara, but songs you might have to visit Baracoa to hear.

On my last day in Baracoa, a bus seat finally being available for the afternoon departure to Havana, I decide to make one final excursion. No time left to visit nearby bays, valleys, mountain passes or archeological sites proposed by Anna and Armando. But the Cueva del Aguas is close enough for a quick visit.

Following my guidebook, I head past the dilapidated baseball stadium and along the beach behind it to find, tucked in a grove of towering palms, a lake spanned by a rickety wooden bridge. On the other side began a long, dirt road that runs past idyllic farmsteads hedged with bromeliad and poinsettia.

About an hour into my walk, I arrive at the Delgado homestead, where a young man in a faded Florida Marlins cap leads me through a yard full of goats and turkeys down to the rocky terrain separating his farm from the ocean.

Nestled amongst scrubby vegetation was the mouth of the Cueva, a cave sloping deep into the earth, at the bottom of which was a pool of cool, clear water. Perfect for a dip, and more so by torchlight, which the young man provided with a kind of tamed Molotov cocktail in a beer bottle.

When I returned to town, it was nearly time to catch the bus. After collecting my things from my casa and promising, at the behest of Anna and Armando, to return, I took a bicycle taxi to the station and soon found myself back on Malecon. The sky was clearing and the sunlight could be seen glinting sharply off the Atlantic.

You've enjoyed Baracoa? my driver asks as he pedals.

Very much, I tell him.

You'll return?

I hope so.

A high wave broke hard against Malecon, and the salt spray settled delicately on my skin.

Soon after he arrived, Columbus described Cuba as "a land to be desired and once seen, never to be left."

The sentiment, particularly with respect to Baracoa, still holds true. Except, sadly, the part about never leaving.

IF YOU GO

Transportation within Cuba

Bus: Daily departures from Santiago de Cuba to Baracoa at 7:30 a.m. with return at 2:15 p.m. on Viazul bus line.

Air: Cubana runs a flight from Havana to Baracoa on Thursday and on Sunday, departing at 8 a.m. and 7 a.m., respectively, and from Baracoa to Havana, on the same days, departing at noon and 11:40 a.m.

Travel agency: In Baracoa, book excursions with Cubatur at 181 Calle Marti, and also reserve bus and air tickets.

Finding accommodation: Try Lonely Planet's Guide to Cuba (2004) or go to http://users.pandora.be/casaparticular/. Book ahead, or be mobbed at the bus station by eager casa proprietors.

Costs: A room in a casa particular, even during the high season, shouldn't cost more than $20 (convertible pesos, pegged to the U.S. dollar).

For the flight to or from Havana with Cubana, expect to pay $128 to $135. For the bus to Baracoa from Santiago de Cuba, with Viazul, I paid $15 one way. The Astro bus line to Havana operates primarily for Cubans, but will sell a limited number of seats to tourists. I paid $53, also one way.

Prices of excursions vary considerably. For El Yunque, I paid $16, and for Parque Nacional de Humboldt, $24. |