|

|

|

Travel & Outdoors | June 2006 Travel & Outdoors | June 2006

Darkness Beyond Cancun's Beaches

Chris Hawley - Arizona Republic Chris Hawley - Arizona Republic

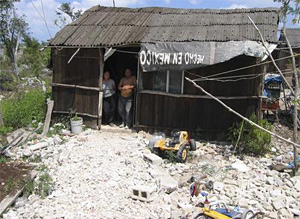

| | Jorge Balam Cen and his wife, Susana Ek, find tourism jobs are hard to get. (Chris Hawley/The Arizona Republic) |

Mexico's model resort city hides an undercurrent of crime and poverty

Cancun, Mexico - Cancun is a place of brilliant turquoise waters and cool white sand, tropical breezes and icy margaritas, glittering hotels and immaculate streets.

That's the Cancun seen by some 4.6 million visitors a year, making this tiny island one of the world's biggest tourist destinations, a major source of cash for Mexico and the model for new resorts from Tunisia to Thailand.

But there's another Cancun just beyond Kilometer Zero, the place on Kukulcan Avenue where the vaunted Hotel Zone ends. And things are not so idyllic there.

It's a city of 500,000 struggling with the social ills of a frontier boomtown: crime and poverty, drugs and gangs, political unrest and a child porn ring whose alleged leader is now in jail in Arizona.

It's a place of gritty "superblocks" where hotel workers live in cinder-block houses, and of even poorer areas where squatters build shanties out of scrap wood and old advertising banners.

"If the tourists knew where we live, they'd understand what Cancun is really like," said María Eternidad Jiménez Orinano, standing in the door of her scrap-metal home in the Tekach neighborhood.

Cancun wasn't supposed to be this way. When the Mexican government carved this resort out of the jungle in 1974, it was seen as a grand new invention in urban planning: an artificial city that would serve as a "pole of development" for the impoverished state of Quintana Roo.

But while Cancun the resort has been a runaway success, Cancun the city has problems. And because Cancun is a model for resorts worldwide, sociologists and urban planners are beginning to take note.

"Cancun is suffering very serious urban problems, along with a kind of polarization and social asymmetry," said Eduardo Torres Maldonado, author of a book about the development of Quintana Roo. "We have people who live in the poorest circumstances working in luxury hotels."

Artificial paradise

In the late 1960s, Mexican government planners set out to build the perfect vacation spot from scratch. They picked the most remote, undeveloped place they could find: a tiny barrier island on the east coast of the Yucatan Peninsula.

The island was called Cancun, "snake's nest" in Mayan. The nearest town, Puerto Juárez, had only 117 residents.

Tourists could stay on the island and never have to see the rest of Cancun city, which would be created solely to serve them.

"The way it was planned originally was to have sort of this nice enclave, this bubble, the island. And then they had this little downtown area for the workers," said Rebecca Torres, a geographer at East Carolina University in North Carolina who has studied Cancun's development.

The government's new tourism development agency, Fonatur, built roads and sidewalks on the island, causeways to the mainland, a water-treatment plant and a world-class airport. Soon hotels were popping up on the island.

The resort was a huge success. Foreigners loved this Disney version of Mexico where you could pay in dollars, speak in English and drink the water. Fonatur took the Cancun model and created four other resorts in Mexico: Ixtapa; Huatulco; Loreto and Los Cabos, which includes Cabo San Lucas.

But Cancun remains the king, raking in more than $3 billion a year and accounting for one-third of Mexico's tourism revenue, a major source of income for the government.

Growing problems

Sitting in his dirt-floor kitchen in the dusty neighborhood known as Superblock 103, former hotel cook Carlos Omar Villanueva reminisced about the days when jobs were easy to get.

"When I came to Cancun in 1983, I didn't even know how to read. I just showed them my birth certificate and they gave me a job," he said.

But as growth has slowed and developers move on to new frontiers, employers in the hotel zone have become more selective.

"Now they want you to have a high school diploma, maybe even know some English. It's not so easy," Villanueva said.

The Mexican government hoped the resort would bring jobs to the poor Mayan Indians of Quintana Roo state.

But most of the Mayans were poorly educated, and they weren't trained for white-collar jobs dealing with English-speaking tourists. Plus, Spanish-speaking hotel and restaurant managers discriminated against them, Torres said.

So the best Hotel Zone jobs went to Spanish-speaking people who flocked in from other states. Today, most Mayans in the Hotel Zone work in low-paying jobs like housekeepers or handymen.

At the same time, wages have lagged behind Cancun's rising cost of living.

Hotel housekeepers earn about 50 pesos a day, or about $5, not including tips. A worker at a McDonald's in the Hotel Zone typically earns $8 a day. But a gallon of milk in downtown Cancun costs $3.60, and a loaf of bread is $1.40. Bus fares are 65 cents, and it usually takes two buses to get from the outskirts of Cancun to the Hotel Zone.

Still, the hope of a job, any job, has attracted hordes of immigrants to Cancun. Most of them live in huge, gridlike neighborhoods known only by numbers: Superblock 106, Superblock 204.

The most recent arrivals settle in shanties on the outskirts of town. The more remote neighborhoods have developed problems with drug peddling and gangs, including one group known as the Hooligans.

The city also has a history of serious drug trafficking. In 2001, federal agents arrested the former governor of Quintana Roo state, Mario Villanueva, in Cancun. The United States is seeking his extradition on charges he protected more than 200 tons of cocaine shipments during the 1990s.

In an interview in March, President Vicente Fox said organized crime was a "serious problem" in Cancun, along with Tijuana, Acapulco and Nuevo Laredo. In April, a federal police commander said he had identified 420 local police who had participated in kidnappings, burglaries and drug crimes.

City officials, meanwhile, say police are poorly equipped to patrol the ever-expanding city. Until this year, Cancun's police force only had 41 operating patrol cars, Mayor Francisco Antonio Alor Quezada said in his State of the City speech in April.

In her book about sex crimes in Cancun, The Demons of Eden, activist Lydia Cacho likens the resort to a town from the Old West. The breakneck pace of development has strained social ties and contributed to lawbreaking, she said.

"Cancun is populated by people who reinvent themselves upon arriving in a community inhabited by strangers," Cacho said. "This phenomenon has generated family dynamics of great loneliness and little emotional attachment to the land that takes them in."

Sex tourism and Arizona

Outside a brothel on the edge of town, a pimp leaned into a visitor's car window and began his pitch: oral sex for $100, regular sex beginning at $250.

"These ladies is clean," he said in English, as three prostitutes in miniskirts watched from across the parking lot. "This is the best place. It's safe; the ladies is clean."

Prostitution, child pornography and even pedophilia parties are another ugly byproduct of Cancun's success.

In the Hotel Zone, taxi drivers hand out color pamphlets showing miniature photos of prostitutes at Pleasure Principle, which calls itself an adult spa. And at 21 Club, a complex of brothels and strip clubs on Lopez Portillo Avenue, there is a steady stream of taxis carrying foreign-looking men.

In April, federal agents arrested an American man, Kenneth Lee Dyer, on child pornography charges after finding videotapes of local girls in his condominium in the Hotel Zone. But Cancun's best-known case is that of Jean Succar Kuri, a Mexican businessman now fighting extradition from Arizona. The case has dominated headlines in Mexico because of Succar's alleged links to powerful politicians.

Mexican prosecutors say Succar used gifts, threats and blackmail to lure poor Cancun girls to his house in the Hotel Zone for sex with him and his friends.

They have charged him with corruption of minors, statutory rape, child pornography and indecent abuse.

Succar fled to the United States in 2003 before police could arrest him, but he was detained on Feb. 5, 2004 during a traffic stop in Chandler. Critics like Cacho, the activist, say Cancun has become a center for sex tourism, and blame authorities for turning a blind eye for decades.

"Cancun has become a center of pederasty, and why? Because of the weakness of the state and the authorities, and because of corruption," said Torres Maldonado, the professor.

Dirty politics

Outside Cancun's City Hall, a tough band of protesters occupies a tent draped with posters and banners. One of them reads: "Chacho: a political prisoner."

"Chacho" is former mayor Juan Ignacio García Zalvidea, who was forced out of office by a mob that surrounded City Hall and pelted it with rocks and sticks on July 16, 2004. He later regained office and finished his term, but has been jailed since November on corruption charges.

The explosion of political unrest in 2004 prompted a warning from the U.S. Embassy about "spontaneous violence" in the city, something unheard of in Cancun. The resort that was meant to be a dreamy refuge from reality had become a political powder keg.

"They were throwing rocks, there was tear gas," said Concepción Colin, a former city councilwoman who holed up in City Hall during the 2004 siege. "It was unbelievable. You shouldn't have political violence in a place like this."

The controversy began after the national leader of the Green Party was secretly videotaped discussing a possible bribe to help a developer win a building permit in Cancun.

The scandal caused a rift between city council members, paralyzing the government. The mayor's supporters accuse the governor of sending union members to surround City Hall and take control of the government by force. A court ruling returned the mayor to power 45 days later.

Supporters say the corruption charges against García Zalvidea are aimed at keeping him from running for governor.

"Our politics are a disaster," said demonstrator Sergio Méndez Áviles, as a bus full of tourists rolled by the protest tent.

Mixed success

City officials maintain Cancun's problems are no worse than any other growing Mexican city. Besides, few tourists will ever see the grittier side of Cancun.

But the resort's image has taken some hits recently. In October Hurricane Wilma struck the city, triggering an outbreak of looting and prompting the Mexican government to send in hundreds of federal police to help keep order.

Then two Canadian tourists were brutally killed in their hotel room in the Barceló Maya Beach Resort in February. The killings actually occurred 40 miles south of the city, but Canadian media refer to them as the "Cancun slayings," and the city saw a dip in Canadian visitors.

Cancun is vulnerable to bad publicity because it has no other industries other than tourism, said Michael Clancy, author of Exporting Paradise, a book about planned tourism in Mexico. The other big city in the Yucatan Peninsula, Merida, has attracted dozens of factories in recent years, but Cancun has none. The area's agriculture has mostly disappeared, too.

Sociologists and urban planners are watching Cancun closely because the Mexican island and its "tourist bubble" have become a popular pattern for resorts in developing countries around the world, Clancy said.

About half of Cancun's hotels are Mexican-owned, a 2000 study found, so much of the profits have stayed in the country. But those profits mainly end up in the ultrarich suburbs of Mexico City, not in the pockets of local Maya.

"Mexico was kind of a pioneer," Clancy said. "But one of the criticisms of tourism in the global south is that it creates this sort of dualism: The money is there, but who is it benefiting? That's the question."

Reach the reporter at chris.hawley@arizonarepublic.com |

| |

|