|

|

|

Travel & Outdoors | January 2007 Travel & Outdoors | January 2007

Mexico's Imposing Peaks a Rock Climber's Dream

Nicholas & Joshua Parkinson - Express-News Nicholas & Joshua Parkinson - Express-News

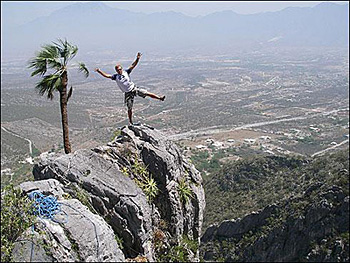

| Climber Joshua Parkinson finds a lone palm tree on the 'airy' top of the multipitch sport route Estrellita in Potrero Chico.

If you go

Lodging In Potrero Chico: Homero's Climbing Camp is near the entrance to the park. The comfortable posada is equipped with a swimming pool, two kitchens and air-conditioned rooms. You can either sleep in a bed for $10 U.S. or camp out under a tree for $3 a night. Climbers can warm up on the several campus boards and pull-up bars hanging in the social area, or just sit down with a pile of recent climbing magazines left for the picking.

For the past 10 years, Homero's has had the dubious distinction of throwing the wildest New Year's Eve party on the map, replete with mariachi, carne asada, Mexican beer and a very special cactus juice. The 'Gringo Disco' reached epic proportions on Y2K when hundreds of climbers and curious mystics showed up to dance below the limestone mass.

For more information: www.potrerochicoclimbing.com

For general information: www.xpmexico.com for climbing/hiking in Mexico

Yosemite Decimal System for climbers

The Yosemite Decimal System is the North American rating system. The first number in the YDS designates the class of the climb (always '5' for free climbs), the second number defines the difficulty. Although the YDS is the most popular rating system in North America, other systems exist.

Vertical climbs that require a rope usually begin at 5.6 or 5.7, and the most difficult climbs go up to 5.14d. |

Imagine holding onto the side of a building 15 floors up and knowing that any slip will send you plummeting to the sidewalk below. Now replace the sidewalk with a deep canyon and the building with a sheer limestone cliff and you will imagine exactly what Mexican climber Alejandro Fuentes faced at mid-morning on July 10 in Potrero Chico, near Monterrey, Mexico.

"There was no one in the canyon that day," said Fuentes. "It was empty and mute."

Fuentes, 26, was free-soloing (climbing without a rope) when something went wrong. A piece of the rock he was hanging from gave way and he fell 30 feet to a lower ledge. The impact tore the meniscus in his left knee and several other ligaments in his legs. Despite his injuries, Fuentes proceeded to climb down the remaining 200 feet of the route and then crawl a half mile back to Homero's, the hostel where he was staying.

We'd met Fuentes at Homero's two weeks before his fall. My brother and I were at the beginning of a three-week climbing trip through Mexico when we pulled into the posada in search of accommodations. We, too, had come to climb the world famous limestone cliffs of Potrero Chico.

Potrero Chico

Six hours south of San Antonio by car, the jagged peaks of Potrero Chico rise over Hidalgo de Nuevo Leon, a village of 20,000 known for the first ever Cemex cement factory.

A series of wobbly Potrero Chico signs gets climbers to the rocks pointing to the heavens. The world-class climbing area has long been a haven for Texas climbers, especially in the winter months. Its limestone peaks rise 2,000 feet above the valley floor and offer more than 300 bolted climbing routes. Many of the routes are "multipitch," which means they extend hundreds of feet up the steep walls and often require a full day or more to complete.

Potrero's walls were first climbed in the '60s by local climbers. By the end of the '90s, the area's impeccable limestone was attracting some of the best climbers in the world, including living legends such as Tommy Caldwell and Kurt Smith.

Texan Dane Bass also came south to enjoy the limestone cliffs. Bass, 61, relocated to Potrero Chico after becoming fed up with what he calls the "rat-race of American life." Bass is originally from Denton and has been in Potrero since the mid-'90s.

"I realized one day that I was working two jobs to get by in America, and that I'd be happier not working either and just climbing in Mexico," says Bass, who didn't even start climbing until he was in his 40s. Bass lives down the road from Homero's and climbs every day. When he's not climbing, he spends most of his time at the hostel, lying by the pool and working on a new, and much needed, Potrero rock-climbing guide with Fuentes. "You really want to know why I come to Homero's?" asks Bass, winking. "It's because of the pool."

Bass has put up at least 100 routes in Potrero, and he continues to establish more every month. He plans to start a bolting school in the winter to give novice climbers a chance to learn the techniques he's developed over a decade of drilling bolts into stone.

"I won't let any climber go home without having bolted something," says Bass, who claims the local authorities have been supportive because more routes mean more climbers and more climbers means more money for the local economy.

"There's enough wall for everyone out there, just look," exclaims Bass.

The day after we arrived in Potrero, my brother and I hiked up the canyon to climb the classic route Estrellita (Little Star). The multipitch climb follows multiple cracks and slanted dihedrals and tops out at about 500 feet above the canyon floor.

After three hours of mellow and well-protected climbing, we approach the summit, which still seems dwarfed by the surrounding towers. There we find a lone palm tree and below it a log bearing the names and summit dates of other successful climbers. Americans and Mexicans appear to be equally represented.

To the south

Potrero Chico is certainly Mexico's Yosemite Valley, a kind of epicenter for Mexican climbing. The number of climbs it offers and the quality of its stone are unsurpassed in Mexico. But we had long planned to continue south in order to hit other popular crags north of Mexico City. So we loaded up the car and hit the road.

Back in Texas, we had used a helpful Web site to find and map out our trip: www.xp mexico.com. The site was created by Rodulfo Araujo, a 41-year-old sales rep from Mexico City. I interviewed Araujo by way of e-mail.

"I found myself always answering questions about climbing Mexico's volcanoes," wrote Araujo. "Then climbing began to grow in Mexico and people started sending me topos (maps of the routes) to publish."

According to Araujo, rock climbing's popularity has skyrocketed since the professional circuit started holding competitions in and around Mexico City. His bilingual (English/Spanish) Web site has facilitated this rise. Visitors can post trip logs and impressions of climbing areas. They can also network and obtain more data about the climbing trip they might have in mind. We found two areas on the site that piqued our interest: La Peña de Bernal, Mexico's biggest monolith near Querétaro, and south of that, Jilotepec, a crag outside Mexico City famous for its steep conglomerate rock.

Driving south from Potrero Chico, we peer out the windows in hopes of spotting the monolith La Peña. Darkness soon overcomes us and we're forced to spend the night in Querétaro, a colonial city with an exquisite city center.

The next morning we catch our first glimpse of La Peña de Bernal. The huge granite monolith (1,150 feet) towers over the scenic village of San Sebastian de Bernal like a giant over a campfire.

We decide to climb the relatively easy route El Lado Oscuro de la Luna (The Dark Side of the Moon) on the southwest face of the monolith. We summit in less than two hours. Instead of rappelling down the same route, we choose to climb down a series of iron grapas (stairs) set into the stone back in the 1950s. While we don't recommend the descent to all, with a bit of caution it can be done without ropes. After the climb, we relax in the village and enjoy some micheladas (beer): two for 25 pesos. Visitors stare at our harnesses and seem to struggle with the idea that humans actually climb the granite monster lurking above. Next to us, villagers sell opals and rocks from the rich mining area. According to them, the talismans bring good energy to its bearer.

The Peña de Bernal has been the site of traditional festivities and ancestral magic since the time of the Chichimecas, before the arrival of Europeans in Mexico. In fact, during the spring equinox, shamans and their followers hike high up the Peña to get their fill of positive energy.

Place where the corn is born

With our positive energy tanks full, we head further south to the cliffs of Jilotepec, just an hour outside of Mexico City. The crags here are tucked away in a highland canyon above the town of Jilotepec (an ancient word meaning "place where the corn is born").

The crag seems small but has ample room for camping. The weekends are often crowded with climbers from Mexico City. The conglomerate rock provides few easy sport routes and enough climbs in general to stay a few months.

Tío Jesús, the park's caretaker, has the key to open and close the gate. After paying him a fee of 10 pesos ($1 U.S.), we are allowed to stay as long as we like. The camping at Jilotepec is serene, and with some help from friends, firewood is abundant. Later that night, the full moon's beams finally find their way to the canyon floor by 2 a.m., and the campground seems like it has been converted into a parking lot lit with fluorescent lights. One of our group chooses to sleep outside in the middle of an old fountain, the rest of us cozy and warm inside the tent.

We breakfast on tortillas and beans and make our way to the crag El Circo, a steep wall comprising nine 100-foot routes, each with tricky crux moves not to be taken lightly. After repeatedly flailing on La Mujer Peluda (The Hairy Woman), we decide to take her on the next day at daybreak.

After three days in Jilotepec, we begin our trek back through central and northern Mexico. In a way, the road trip is over. We have visited only three crags of the hundreds that dot the Mexican landscape from Baja California to Guadalajara.

Nearing Monterrey, we glance at each other and instinctively know what the other is thinking: "You know, we could climb one more day in Potrero and still make it back to work in time."

And we were back on the Mexican limestone sooner than we had thought.

Nicholas and Joshua Parkinson live in Chile and Kuwait respectively and try to get together to climb somewhere around the world at least once a year. |

| |

|