|

|

|

Travel & Outdoors | November 2007 Travel & Outdoors | November 2007

The Whole Enchilada

Christopher Reynolds - Los Angeles Times Christopher Reynolds - Los Angeles Times

go to original

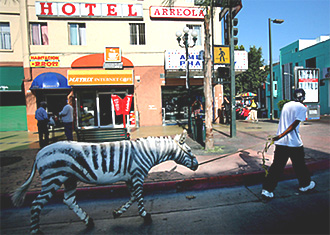

| | A Zebra striped burro walks along Ave. Revolucion in Tijuana, Mexico, August 20, 2006. (Sandy Huffaker/The New York Times) |

Tijuana, Mexico - It's dusk in Tijuana's red-light district, and two bouncers are slouching outside a strip joint called the Chicago Club. A car rolls up, a window rolls down and the American guy on the passenger side starts asking questions in awkward Spanish. Looks like business as usual.

But then I climb out of the passenger seat - that's right, it's me in the car - to make sure they hear me right.

"That sign across the street," I say, pointing toward the towering words 'Molino Rojo' in scarlet neon. "From what year is it?" The guys look at each other. They have seen many things on this block, but an architectural preservation tourist, it seems, is not one of them.

"From the 1930s?" I ask hopefully. They squint across the street and scoff. "Fifties or '60s," one of them finally says.

Bummer. And welcome to the search for the Tijuana of the '20s and '30s - the city that was Las Vegas before Vegas was Vegas, the city that some Tijuanenses pine for and others treat like incriminating evidence. This bygone Tijuana lives on in tattered postcards and historical- society monographs, its casinos paying off in American silver dollars, its horse-track bettors forever tempted by the prospect of a nightcap at the world's longest bar.

Looking for remnants of that place in 2007 is like diving for a Mexican Atlantis. Instead of checking out the hotels and fancy restaurants along the fast-growing Baja coast, you squint at history through a veil of border culture and discarded architecture, the scene scented with carnitas and beer.

If you persevere, you can learn why a Muslim mirage rises over the heart of Tijuana today and how two enduring trophies of 20th-century high life, the Caesar salad and the margarita, were born here.

Tijuana: Inspiration for Vegas

By now, the world takes for granted Tijuana's reputation as a den of forbidden thrills (or, as Krusty the Clown on "The Simpsons" puts it, "the happiest place on Earth"). Until I saw a book by preservationist Chris Nichols titled "The Leisure Architecture of Wayne McAllister," I had not thought about the roots of that reputation or the Tijuana-Vegas connection.

In the course of telling how McAllister landed the job of designing a long-lost resort called Agua Caliente - at the age of 19 - Nichols sketched a bigger picture that explained much.

From 1919 to 1933, alcohol and casinos and prostitution and horse racing were all forbidden or tightly restricted in California - and all were easily available in Tijuana. Because of that, great pleasure palaces were built, including the city's fabled Agua Caliente casino, and countless Hollywood celebrities and their imitators crept south by car, rail, ship and small plane.

The Agua Caliente casino was the crown jewel of the era. It opened in 1928, tiled and stuccoed, Moorish and missionary, vast and self-assured. It lay six miles south of the border, covered 655 acres and cost about $10 million at the time, mostly supplied by American investors.

Writes Nichols, "It was the inspiration for Las Vegas."

Along with a casino offering roulette, baccarat and faro (but no windows or clocks), it featured about 400 rooms and bungalows, a horse-racing track, a golf course, a spa fed by natural spring water, an Art Deco ballroom, various cocktail bars, tennis courts, a riding academy, a landing strip for small planes, a blue-tiled minaret and an iconic bell tower, a replica of which now stands at the beginning of Boulevard Agua Caliente.

Charlie Chaplin and Gary Cooper came to the races. Douglas Fairbanks sat on the board of directors. Jean Harlow tried the golf course. Bing Crosby and Clark Gable saddled up horses, and the showroom featured a teenage dancer, Margarita Cansino, who later changed her name to Rita Hayworth.

Architectural Digest gave it 16 pages in 1929. Hollywood gave it a movie - "In Caliente," featuring Dolores del Rio and Pat O'Brien, shot on location in 1934.

Looking for a lost world

Things began to change in the 1930s. Nevada legalized gambling in 1931. The U.S. ended Prohibition in 1933. Santa Anita racetrack opened near Los Angeles in 1934. In 1935, newly elected Mexican President Lazaro Cardenas banned casino gambling. Tijuana kept attracting American thrill-seekers, and sports betting and several other kinds of gambling have endured. But once the high-end gamblers left, thousands of jobs were lost and the palaces crumbled, burned or were retooled.

I made two trips and enlisted three guides to help me find that lost Tijuana.

At one point, as a guide and I waited in our car at a busy Tijuana intersection, a ball of flame erupted in front of us. Then another.

Then I realized they were coming from the mouth of a roadside beggar. Between fiery bursts, he raised a jug of God-knows-what to his lips.

And then the light changed and my guide hit the gas without even bothering to shrug.

"People breathe fire for money," he said in the tone of an indulgent urbanite tutoring a bumpkin.

Maria Curry, an architectural historian who led me through downtown on another day, takes the opposite tone. "This is a magic place," she says as we pass a workaday scene: the peppers and piñatas of the Mercado El Popo on Second Street. Then she explains its roots (in the market's case, the 1930s).

Old and new Tijuana

Most of the 2 million or 3 million people who live here now (estimates vary) have come from elsewhere in Mexico.

Teniente Guerrero Park was the town's first, founded just a few blocks off the main drag, Avenida Revolución, by a group of female activists in 1924. It remains the same as it was then: chess players, kids wrestling on ragged grass, ancient shoeshine guys, moms pushing toddlers on the swings, and over by the west end, free-lance auto repairmen.

I move on to Hotel Caesar at Fifth and Revolución and order salad in the restaurant. The consensus west of the Mississippi is that the Caesar salad was created in Tijuana in the 1920s and popularized by hotelier and restaurateur Caesar Cardini.

The good news is that after changes in ownership and a lapse in salad-making in the early 1990s, the staffers in the restaurant still make a big deal of whipping up a salad while you watch. At $6 - romaine lettuce and croutons dressed with Parmesan cheese, lemon juice, olive oil, egg, Worcestershire sauce and black pepper - it's a good value. Also, the hotel has finished renovation of the 46 guest rooms, which cost between $35 and $70 nightly.

The bad news is that they over-renovated. Hotel Caesar used to be full of atmosphere and reminders of the days when bullfighters bunked here. Not anymore. Just about every hint of the '30s has been obliterated.

Now, three other casino sites in northern Baja speak most loudly about the old days.

Taking them south to north, you begin 68 miles below Tijuana at a stately property rich in Moorish and Mission flourishes, the buildings surrounded by gardens. This is the Riviera del Pacifico, formerly the Hotel Playa of Ensenada.

Completed in 1930, it stood on the beach and counted boxing champion Jack Dempsey among its original supporters. William Randolph Hearst came, and Dolores del Rio, Johnny Weis-muller and Myrna Loy.

But when liquor and gaming laws in the U.S. and Mexico started changing, the Playa began a long, bumpy ride, mostly downhill, until its last guests checked out in 1964.

The casino building has survived, and what a specimen it is: wormwood beams from Florida, curlicued iron from Havana, a chandelier from Spain - and tiny slits in the main room's ceiling, through which management could peep down upon gamblers below.

Visitors can wander at no cost through the idle spaces . You can wander the gardens too, but every time I strayed onto the lawn to take a picture, a keen-eyed groundskeeper was there to wave me off. Inside, there's a museum, and there's also the Bar Andaluz, which claims to have created the margarita in 1948.

I am suspicious. Just a mile or two north is Hussong's, a cantina that has lubricated Ensenada gringos since 1892. They brag that that a Hussong's barkeep, Don Carlos Orozco, invented the margarita in 1941.

Romp in Rosarito

After the keep-off-the-grass stillness of the Playa/Riviera, I was looking forward to a little noise at the Rosarito Beach Hotel. But I was also a bit afraid. Founded in 1925, the hotel has done so much renovation that it has evolved into a new species entirely.

It has grown from 12 to 231 rooms - no casino, of course, because casino gaming is still banned in Mexico - and you have to hunt for hints of the old days.

There's the entry arch (where, says the decades-old lettering, the most beautiful women in the world pass by), the gardens, the tiled floors, lobby murals and pool from the '30s.

I might not be back for a while; the place is as shrill and garish as the rest of fast-expanding Rosarito. But it has survived, and co-owner Hugo Torres Chabert (who also is the mayor of Rosarito) is clearly as ambitious as his forebears were.

Back to Caliente

I ponied up $11 for the Friday-night buffet and stayed for a folkloric dance show full of thunderous music, stamping feet and flashing colors. But in the end, I sneaked back to Agua Caliente.

The curtain was falling on Baja's golden age by 1938. Fires leveled nearly everything in the 1960s and '70s.

So what about the casino itself, the epicenter of all that was grand about old Tijuana? You can hear the echoes of the '20s.

I advance to the old Olympic-sized swimming pool and a tiled arch, once a spa window, that frames a view of the resort's most visible remnant: the 150-foot tiled minaret.

Now, hundreds of teenagers - students at Lazaro Cardenas High School - lounge beneath towering palms and figs left over from the original hotel-casino landscaping.

In a flurry of recent renovation, workers have refilled the swimming pool and put up more walls and arches as an homage to the old days. I stared into an empty pool like a soothsayer seeking meaning in tea leaves.

I couldn't say what was happening in Las Vegas that afternoon, but I felt, all at once, very close to the place and very far from it. |

| |

|