Mexico's Valley of Wine

Mike Dunne - Sacramento Bee Mike Dunne - Sacramento Bee

go to original

January 07, 2010

See sidebar: Accommodations, Restaurants, Wineries, and More Information

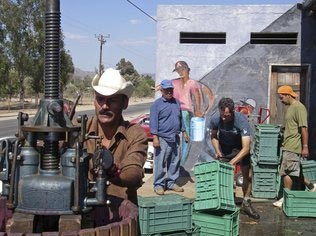

| | Harvest workers keep the wine presses busy at L'Escuelita, a cooperative winery and winemaking school. (Mike Dunne/The Bee) |  |

Valle de Guadalupe, Mexico – Hot, dusty, rattled by rocks and ruts of the road, and as confused as lost conquistadors, we slump into chairs at the reception office of the inn Adobe Guadalupe.

Minerva Cerda, graciously bearing dewy glasses of a bright rosé, materializes immediately through a side door. With the first sip – a gulp, actually – we relax, stop worrying about the car's undercarriage and begin to look more closely at our surroundings.

Though Adobe Guadalupe has just six rooms, it's one sprawling hacienda, with a massive fountain in the courtyard, a winery off to one side, a pool and hot tub on the other, collections of teacups and cut crystal artfully arranged here and there, and three galumphing Weimaraners enjoying the run of the place.

We glance out doorways and windows, seeing vineyards roll in orderly rows across the vast valley floor. It looks like the Napa Valley, but we're in Baja California.

More specifically, we're wrapping up our first day in Valle de Guadalupe, about half an hour northeast of Ensenada, a coastal party town roughly 70 miles south of San Diego.

In Ensenada, the tourist draws are fish tacos and beer. In Valle de Guadalupe, it's wine. There's not much here other than vineyards and wineries, slowly squeezing out the orange and olive groves, alfalfa fields and horse farms that have long set the tone for the valley's rich agrarian history.

Wine lovers won't be disappointed with what they find in the hot, arid Valle de Guadalupe. Although swine flu and fear of violence have deterred many Americans from visiting, we couldn't resist it.

An estimated 80 to 90 percent of the wine made in Mexico is made in Baja California, and most of that is produced by the 30 or more wineries in this valley. The producers range from corporate giants to boutiques no bigger than a one-car garage.

Although most of Baja is desert, Valle de Guadalupe benefits from its proximity to the Pacific Ocean and by topography similar to Santa Barbara County. In both viticultural areas, maritime breezes stream east though a gap in the coastal hills and are more or less confined by ridges, providing cool breaks from torrid temperatures, helping maintain the sugar and acid balance crucial for expressive wine grapes.

Wineries are apt to be far back on a washboard road or tucked in a ravine up a tortuous path best traversed with a high-riding four-wheel-drive beater.

"I like to tell people that this is off-roading in the wine country," says Steve Dryden, a retired U.S. National Park Service naturalist who came here a decade ago to write about wine and guide tours.

Our first stop on Day 2 is Vinicola L.A. Cetto, one of the larger and more historic wineries in the valley, dating from 1974. Out front, members of the Kumai tribe oversee a table at which they sell bundles of fresh rosemary and sage, and baskets woven with pine needles.

Inside, Camillo Magoni, the native Italian who has been Cetto's winemaker from the start, is lining up bottles to showcase the winery's portfolio, from an inexpensive everyday petite sirah to a pricey blend of cabernet sauvignon, nebbiolo and montepulciano he makes every five years to salute the winery's founder, fellow Italian Angelo Cetto.

"Mexico is known for tequila, beaches, archaeology, Corona and spring break, and in the near future for wine, I hope so," says Magoni.

He's been involved in the valley's wine trade since 1965 and has seen it evolve from a focus on large yields for simple brandy to today's intensifying concentration on small yields, premium varietals and high-end proprietary blends. The brandy has all but disappeared, succeeded by dry table wines, Magoni says.

"This is the best area in Baja for wines, but it's not the only one," he boasts, noting that such neighboring valleys as Las Palmas to the north and Santo Tomas and San Vicente to the south also yield fruit for fine wine.

While demand for Mexican wine is growing, particularly in Mexico City, Guadalajara and resort cities with a sophisticated and affluent clientele, vintners say, Baja's wine trade is hamstrung by forces natural and bureaucratic. Drought, coupled with Ensenada's tapping of the Guadalupe River, is keeping growers from expanding for fear they won't have adequate water to irrigate their grapes.

And then there are Mexico's mysterious, cumbersome and onerous wine taxes, which inflate the price of a bottle between 35 percent and 40 percent if it is sold beyond the winery.

"It's almost impossible for a winery our size to comply with the federal regulations to get that government sticker so we can sell to hotels and restaurants," says Miguel Fuentes, vineyard manager and winemaker at his family's Vinos Fuentes winery on the southern outskirts of Francisco Zarco.

"Producing grapes, making your own wine, and selling your wine on your own property is a lot easier to do," adds Fuentes, a Mexicali native who graduated from UC Davis with a degree in international agriculture development in 1992.

Like several of the valley's other boutique vintners, he's hoping the area continues to develop the infrastructure to become as well-known as an appellation as it is as a day trip for tour groups out of Ensenada.

But today, Valle de Guadalupe is a rustic wine region with just a handful of posh accommodations and only a couple of restaurants with ambitiously artistic food. Like the Napa Valley of half a century ago, it is occupied primarily by farmworkers and pioneering winemakers, and only essential businesses – the Pemex gas station, mini-markets, panaderias, taquerias. Fashion boutiques and spas are a long way down the road.

Wine enthusiasts who want something to do after they've exhausted their palates pretty much are limited to horseback riding, mountain biking and hiking, or they can head to Ensenada for sport fishing or golf.

On the other hand, anyone seeking a change of pace from the competitiveness and congestion often encountered in Northern California wine regions, as well as some welcome solitude, will find Valle de Guadalupe comforting – unless they step out of the car and almost get hit by a youngster galloping by on his horse, as happened to me in Francisco Zarco.

"Most guests have an agenda when they get to the valley, but once they get to our place they stay and relax," says Nathan Malagon, whose family's Vinedos Malagon includes a small and secluded bed-and-breakfast bordering an old grenache vineyard tucked up against the foothills just to the north of Francisco Zarco.

Not that Valle de Guadalupe entirely lacks archaeological, historic and cultural attractions. The most curious stem from the immigration in 1905 of Russian Molokans, pacifists who fled the mother country rather than fight for the czar. They congregated just southwest of Francisco Zarco, in an area to become known as El Porvenir, or "the future."

Today, the valley has three small Molokan museums, two across the street from each other in Francisco Zarco, where the cemetery has almost as many headstones in Russian as Spanish. (Explanatory signs in the museums, however, invariably are in Spanish and Russian, not English.)

The third museum is at Vinos Bibayoff, owned by David Bibayoff Dalgoff, a member of one of the last two Molokan families in the valley, in Rancho Toros Pintos, just south of Francisco Zarco and El Porvenir.

Dalgoff, who in the winery's museum shows off the framed government permit his grandfather, Alexie M. Dalgoff, got in 1931 to make wine, tends 40 acres of grapes, most of which he sells to other vintners. Under his own label, he makes a fleshy and herbal cabernet sauvignon, a sweet zinfandel and a spicy port.

Big and convivial, Dalgoff represents the relaxed and casual attitude of much of the valley's wine community.

"When the gate is open, we are here," says Dalgoff, when asked when Vinos Bibayoff is open to the public.

No less enamored with Valle de Guadalupe's wine prospects is ceramic artist Ivette Vaillard, who moved into the valley from Veracruz 27 years ago, acquired a half-acre of hardscrabble hillside and without electricity began to plant pomegranate, macadamia, walnut, olive and pear trees, the fruit of which she sells at the local farmers market.

She also began to cultivate wine grapes and with two other women created Tres Mujeres Winery. They make mostly perfumey and juicy cabernet sauvignons. They sell their production out of their cellar, where they tunneled deep into the granite under vineyard and orchard to scoop out one of the few wine caves in the valley.

Throughout my tastings I'd been trying to pin down stylistic threads that tie one wine to another in hopes of understanding what sets apart the wines of Valle de Guadalupe from releases in other regions. The task is complicated by the wide variability in style and quality among producers.

Some are as coarse as wines made by a not particularly attentive home winemaker, while others are startling for their complexity, elegance and balance.

When I ask vintners what broadly distinguishes the wines of Valle de Guadalupe, they also struggle to come up with an answer, an indication of the region's youth and continuing experimentation. Ivette Vaillard, on the other hand, nails it: "Compared with other countries, they are heavy wines, they have a lot of body."

True, regardless of whether the wine is white, rosé or red, varietal or blend, dry or sweet, the wines of Valle de Guadalupe tend to have a richness to them, a fleshiness, a ripeness stopping just shy of being overripe. That's generally speaking. Exceptions can be found, such as that lean, crisp and spicy rosé that first welcomed us into the area at Adobe Guadalupe.

See sidebar: Accommodations, Restaurants, Wineries, and More Information |