|

|

|

Editorials | Opinions | April 2007 Editorials | Opinions | April 2007

Blood and Murder: All in the Plaza

Kyle Sheahen - cornellsun.com Kyle Sheahen - cornellsun.com

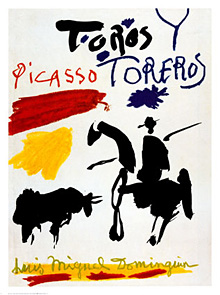

| | Bull with Bullfighter by Pablo Picasso |

Historically, the Romans had the Coliseum, the Church had the Inquisition and we have Todd Bertuzzi. Our airheaded masses howl as boxers bludgeon brain cells or NASCAR drivers implode into oblivion.

For the truly twisted, however, nothing compares to the joyous savagery of a Mexican bullfight.

La Corrida involves the ritual murder of El Toro Bravo — a Spanish bull with mystic significance.

The origins of this macabre spectacle are not clear. Bull sacrifices are mentioned in ancient Greek mythology and the Bible. The bullring — or plaza — could be Roman, Greek or Iberian in design. The sport is presently claimed by the Spaniards and was imported to Mexico along with the conquistadors and genocide.

On a given day, separate toreros can slaughter any number of bulls. In the local plaza this past month in Puerto Vallarta, the magic number was five.

The setting at the bullfight stadium was surreal — something out of Guillermo del Toro’s next film. Local families snatched front row seats as disquieted tourists sought 10 peso Coronas to settle their nerves. A mariachi band played dark ceremonious music like a high school marching band in a slasher flick.

There was a guy who looked like Danny Trejo on acid. For a few pesos he allowed passers-by to pet his enormous iguana.

The arena itself reeked of sweat and blood. It was a dirt oval about the size of three wrestling rings. To the south was an enormous gate with an eerie, industrial-strength chain hanging behind it.

The gate was where the bulls entered the arena; the chain was what they hanged from after they died.

No one would say the battle between man and beast is fair. Before el toro enters the arena, it is stabbed once or twice in the side. At first, the wounds anger the bull and the animal rampages in the dirt. As La Corrida continues, however, the steady trickle of blood from the wounds slows the toro and eases the torero’s ultimate task.

As the mariachi band blares on, horsemen — known as picadores — circle the bull and drive lances into its back. Again, not exactly a fair fight.

To the delight of the locals in Puerto Vallarta, one picadore was bucked off his horse by an attacking bull. The tourists seemed to gulp their Coronas more briskly.

Payback for the picadore came when the banderilleros came out. These are bullfighters on foot who dance around their target with two small, multicolored spears. If he knows what he’s doing, a banderillero will stick both spears into the bull’s neck; if he doesn’t, he manages only one spear or get chased out of the ring.

Vendors in the crowd sell replica spears to children as the fight enters its final stage.

It is now just the torero and the toro in the suerte suprema. The torero holds a red flag in front of the bloodied and struggling bull, enticing the animal to charge but always pulling the flag away. The flag is held up by a silver sword that brilliantly reflects the afternoon sun.

Time after time the bull lunges and misses. With each miss, the torero drives the sword into the bull — sometimes in the side, other times in the neck and head. As the bull slows the torero taunts it, turning his flag and sword routine into a dance of death.

Finally, the mariachi music stops and silence grips la plaza. The staggering toro has fallen and the torero holds his sword above its brain. A single trumpet pierces the silence with a high note and the torero delivers the fatal stroke.

The bull is dead.

The locals applaud, the torero bows, and the tourists — somewhat aghast — cannot believe their eyes or ears. They look on in awe as the bull’s corpse is dragged from the ring and strung up on the chain behind the gate.

This is only the first killing of the day. The spectacle is repeated four times as tourists go from Coronas to tequila shots and in a bacchanalian haze begin to revel in the gore.

At day’s end, everyone snaps photos with the rock star toreros. The bright outfits, the music, the dancing, the colors, the sun setting over the ocean all blend together in a vibrant kaleidoscope.

Somehow, La Corrida is no longer obscene. It is not even mere sport. Like Picasso at his most bizarre, La Corrida has become art.

Sheahen can be reached at ksheahen@cornellsun.com |

| |

|