|  |  |  Editorials | Issues | September 2008 Editorials | Issues | September 2008

Remembering the 1968 Massacre at Tlatelolco

Ed Hutmacher - mexicobookclub.com Ed Hutmacher - mexicobookclub.com

| | Plaza de las Tres Culturas 1968, moments before troops and police opened fire on student protestors. |

| | A 2006-07 special prosecutors report confirmed that the deadly gunfire came from gov't troops. |

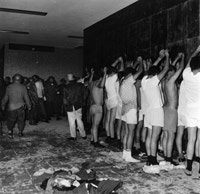

| | Captured students were stripped, beaten and later charged with inciting violence and subversion. |

| | Photos of the dead show that students were brutalized; many were repeatedly stabbed with bayonets. |

| | 1993 monument in Tlatelolco Plaza honors those who died during the October 2, 1968 massacre. | | |

Forty years ago on October 2, just ten days before the start of the XIX Summer Olympics in Mexico City, the most spectacular instance of state violence in post-revolutionary Mexico took place at the capital's Plaza de las Tres Culturas in Tlatelolco when government troops and police opened fire indiscriminately into a crowd of student protestors and bystanders, killing and wounding scores of people.

At the time and for several decades afterwards the ruling PRI government kept details of the bloody confrontation shrouded in secrecy, claiming that armed students provoked the gunfight by firing on police and that the death toll was more or less a mere 30 people. Observers in the plaza that day disputed the government's claims, saying at least 300 people died.

"What is certain," said Mexican journalist and author Elena Poniatowska, "is that those who fired on the crowd, those who carried out an encircling action to trap them, were military forces."

Poniatowska spent three years collecting details on everything that was not secret and wrote a gripping account of the incident in her 1971 book La Noche de Tlatelolco (published in English as Massacre In Mexico; University of Missouri Press; 1992). In it, Poniatowska assembled a montage of testimony drawn from participants and eyewitnesses to the violence: surviving students, parents, journalists, professors, priests, even police and soldiers.

Strung together, the testimonials reveal a chaotic, optimistic naiveté on the part of the upstart student protestors pitted against the calculating, heavy-handed modus of an entrenched patriarchal PRI regime. Antagonism reached a fevered pitch when paternal patience turned brutally intolerant.

The tragedy began when some ten thousand students rallied at Tlatelolco plaza, calling for greater democracy and reform of the authoritarian PRI government. Although months of nation-wide student strikes had prompted an increasingly hard-line response from PRI President Diaz Ordaz's government, no one was prepared for the bloodbath that Tlatelolco became.

Shortly before 6:00 pm, just as the generally peaceful demonstration was wrapping up, a military helicopter hovering above the plaza dropped a signal flare. Hundreds of heavily armed troops, riot police and plainclothes soldiers emerged from behind balustrades and buildings and opened fire on the crowd. Hysteria erupted. Tanks mounted with machine guns immediately surrounded the plaza, spraying bullets and preventing escape.

The carnage lasted about ninety minutes. When the shooting stopped, bodies of the dead and wounded littered the plaza.

Security forces seized upwards to a thousand surviving protestors and dragged them away. The arrested were stripped of their clothes, beaten and later charged with inciting violence and subversion. Student leaders and others served prison sentences ranging from three to seventeen years. Some of the dead and arrested simply disappeared, never accounted for again.

"From that moment on," said Poniatowska, "the lives of many Mexicans were divided in two: before and after Tlatelolco."

It took time for most Mexicans to absorb what happened at Tlatelolco and why it even mattered. Eventually, Mexicans became at once shocked and outraged by the government's brutal authoritarianism, its secretiveness, its duplicity, its ongoing "dirty war" against dissidence of all stripes.

Poniatowska would later call Tlatelolco a "watershed event" in Mexico's historical struggle for democracy. Other Mexican writers have likened Tlatelolco to the violent debacles at Kent State in the United States and Tiananmen Square in China: a frantic response by a government that felt the student movement was a threat to their grip on power.

It took another thirty-two years before the PRI finally lost its uninterrupted seventy-one year grip on power. In 2000, opposition candidate Vicente Fox was elected president in a momentous victory that ushered in a new era of hope for a country yearning for political reform and answers to decades-long questions.

In 2002, Fox appointed a special prosecutor to investigate the Tlatelolco killings and other incidents of the PRI's dirty war. In a report released last year, special prosecutor Ignacio Carrillo confirmed what had long been believed—that the deadly gunfire indeed came from government security forces, some 360 sharpshooters surrounding the plaza. Carrillo also accused Luis Echeverria, the interior secretary responsible for domestic security in 1968 and the second most powerful official in Diaz Ordaz's administration, of masterminding the government's strategy, but said it was "highly probable" that Diaz Ordaz himself ordered the assault.

Echeverria broke thirty years of silence on the Tlatelolco massacre in a rambling 1998 interview, saying that Diaz Ordaz, who died in 1979, was the only person who could have ordered government forces to fire on the demonstrators.

"There was a hierarchy. The army is obligated to respond to only one man," Echeverria said. "My conscience is clear."

Still, according to Carrillo's report, the most brutal human rights violations allegedly occurred during Echeverria's 1970-1976 term as President. Carrillo first sought Echeverria's arrest in 2004 in connection with another student massacre in 1971 (in which two dozen student protestors were killed) and for the disappearance of up to 148 political leftists during his term. All of the charges were thrown out or blocked by courts.

Left uncertain in Carrillo's report is the number of people killed at Tlatelolco Plaza. The special prosecutor found evidence of only thirty-eight deaths, a number that corresponds to the names on a monument erected in 1993 to honor the victims.

Were more killed? Was there any truth to stories claiming government troops secretly carted off and dumped bodies in the ocean? As with any calamity, we may never know the answers.

In the meantime, Mexicans are still reeling from the black eye—the wound in the national conscience. The celebration of an anniversary such as the Tlatelolco massacre reveals a country still coming to grips with its history as much as its ongoing struggle for democracy and social justice.

As Mexicans commemorate the fortieth anniversary of that fateful October 2 day, several things come to mind, each a powerful reminder to all of us:

Liberty comes at a high cost. Truth is hard to come by. Heroism is worth remembering.

Ed Hutmacher is Editor in Chief of MexicoBookClub.com. |

|

|  |