|  |  |  Editorials | Issues Editorials | Issues

Get Shorty: Mexico Still Searching for ‘El Chapo’

Hannah Strange & Ruth MacLean - Times Online UK Hannah Strange & Ruth MacLean - Times Online UK

go to original

March 02, 2010

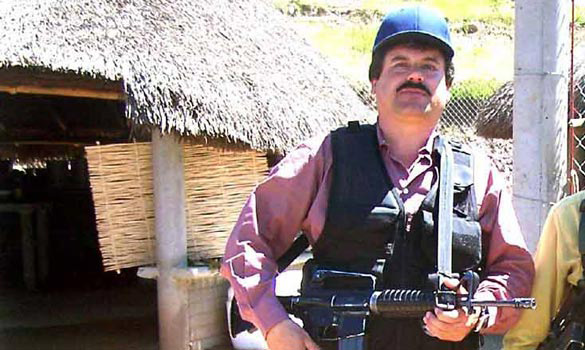

| | Joaquín 'El Chapo' Guzmán, head of the powerful Sinaloa cartel |  |

In the remote, rough terrain of the Sierra Madre mountains in the state of Sinaloa, Mexico’s most wanted, most feared and most elusive drug lord is hiding.

Protected by a sophisticated reconnaissance operation with deep roots in the local population, he has been evading Mexican and US authorities since his escape from prison in 2001. Those who watch out for him are known as “rats”: taxi drivers, street sellers, shoe shiners, delivery men — “anyone equipped with a phone who wants to earn a few dollars” by informing on military or police activity, says José Ramón Salinas Frias, chief spokesman for the Public Security Secretariat.

The mountains are beautiful but nearly impossible to navigate. The forests are quickly disappearing into the mills of illegal loggers, and with them disappear the wild boar that the local people hunt. Many of them have become drug farmers, growing marijuana or opium. They are well armed and they do not like outsiders.

Trying to capture the narco-king has been likened to the pursuit of left-wing guerrillas in the Colombian jungle — and certainly he has acquired an element of the renegade’s mystique. Immortalised in the ballads of the narco-corridos — musicians who specialise in the exploits of drug gangsters — he has become embedded in popular legend as a 5ft 6in Houdini with guns.

Amid the fury and violence of President Calderón’s war on the cartels, some mighty kingpins have been toppled, but one man stands out as the scourge of pursuing forces: Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, head of the powerful Sinaloa cartel.

Occasionally he is sighted. Local rumour has it that he once went to a restaurant, confiscated all the diners’ mobile phones while he enjoyed a steak and then left after returning each phone to its correct owner. The diners later discovered that their bills had been paid.

In 2007 he married his third wife, a local beauty queen called Emma Coronel Aispuro, on her 18th birthday, in a lavish wedding that could have graced the pages of the glossiest society magazine. Despite the high levels of security and protection, local politicians and police officers were reported to have attended.

Since then his wife has often been seen in beauty salons in Culiacán, surrounded by high security. But, as the fervour to catch El Chapo increases, he becomes an ever rarer sight — perhaps, in part, as he is said to have had substantial facial reconstruction surgery.

Despite a $5 million (£3.3 million) bounty offered by the United States and another $2 million by Mexico, El Chapo — or Shorty — has given agents from both sides of the border the slip for nine years, since his escape in a laundry basket from the maximum-security Puente Grande jail.

As a child he sold oranges to get enough money to eat. Now, at 52, Guzmán is No 701 on the Forbes list of the world’s billionaires, with an estimated $1.1 billion fortune garnered from running Mexico’s most brutal and profitable business. In addition to the drugs that made his name, Guzmán specialises in human trafficking, money laundering and several other types of crime, with international networks spreading their tentacles throughout the world.

He goes about his business with impunity, afforded by a potent mixture of money, ruthlessness and trickery. Protected by foot soldiers who behead or torture anyone who might pose a threat, and with almost limitless financial power, Guzmán operates with relative freedom in his home state of Sinaloa.

US drug officials believe that corruption within the Mexican authorities is a key factor in his ability to evade capture.

Last March, in an interview with the respected Proceso magazine, Anthony P. Placido, intelligence chief for the Drugs Enforcement Agency, said that “none of the kingpins of the drug cartels” felt seriously threatened by Mr Calderón “because they have broad powers of corruption that give them a kind of immunity, we say, guaranteed”.

He raised specific concerns over rumoured links between close associates of Genaro García Luna, the Public Security Secretary, and criminal groups.

A senior US law enforcement official in Mexico, speaking to The Times on condition of anonymity, acknowledged concerns that Guzmán often slipped through the authorities’ hands because of tip-offs from corrupt officials.

“There is public corruption and they will utilise it, whether it’s bribery, intimidation or the threat of killing people,” he said. The Public Security Secretariat had had cases of corruption, the official acknowledged — but it was difficult to say that it was “worse than anyone else ... it’s a concern everywhere”.

An orchestrated balance of fear and respect also plays its part. On the one hand, terrorising rivals with kidnapping, killings and tortures — the cartel is said to dissolve victims’ bodies in acid — and on the other building loyalty in his communities by funding new schools and churches, Guzmán has become part-monster, part-hero; a powerful combination that keeps his whereabouts shrouded in silence.

In March last year Archbishop Hector González Martínez of Durango, the state bordering Sinaloa, claimed to know Guzmán’s location. “El Chapo lives a bit beyond the town of Guanaceví. Everyone knows that — well, everyone except the authorities,” he said. Four days later the bodies of two dead lieutenants were found outside Guanaceví with a note: “Nobody can catch El Chapo — not the authorities, not the priests.” The Archbishop later retracted his statement, saying that he had just been repeating rumours.

“Guzmán is the only drug boss that has built his company like a government,” said Raúl Benítez Manaut, a national security and drug trafficking expert at the National University of Mexico.

“He has military protection, an army of administrators, many legal companies to launder money and many houses in and outside Mexico — apparently he has property in Central America. In Sinaloa he controls a lot of the economic activity.” He is a symbol of the growth of organised crime in Mexico and the Government’s failure to contain it — so, as with Osama bin Laden, another mountain fugitive, Guzmán’s capture would be a glorious victory for either US or Mexican forces.

But while it would send an important message, some say that it would do nothing to dismantle the Sinaloa cartel. “You won’t destroy them just by incarcerating El Chapo Guzmán,” said Edgardo Buscaglia, an organised crime expert at ITAM University. “The Sinaloa cartel is a business. It has a board of twelve members — only four of whom are well known — and all 12 are equal in power. Guzmán could be replaced in a few weeks.”

US investigators take a different view. They agree with the Mexican analysis that power is concentrated in the hands of Guzmán and his partner-in-crime, Ismael Zambada García, and that Zambada could still run the cartel, but the symbolism of Guzmán’s arrest should not be underestimated.

In Mexico there was a public perception that men such as Guzmán had the type of reach that would always allow him to beat the system. “If El Chapo fell out [of the drugs business] it would be huge,” said the US official.

He gave the example of Arturo Beltrán Leyva, a former Sinaloa leader who formed a breakaway cartel. His death in December at the hands of Mexican agents dispelled the illusion of invincibility surrounding such figures, he said, demonstrating that “Calderón is not messing around”.

Mexican and US forces believe that they are gradually closing the net. There have been other recent successes: last week José Velázquez Villagrana, an important trafficker within the Sinaloa cartel, was arrested; the notorious hitman Teodoro García Simental, known as “El Teo”, was captured last month. “The arrest of each of these principal pieces will at some point lead to the arrest of its head,” said Mr Salinas Frias.

As Mexico’s drug war drags on, however, Mr Calderón faces critics who say that his deployment of the army has been disastrous — 18,000 people across Mexico have been killed in drug-related violence since late 2006 — and some who allege that the Government protects the Sinaloa leadership.

More have died recently as Guzmán fights a turf war with Vicente Carrillo Fuentes, leader of the Juárez cartel, in Ciudad Juárez, where more than 4,600 people have been killed over the past two years.

For most Mexicans, drugs are everywhere, sold not-so-secretly in markets, by taxi drivers and random moustachioed men in Hawaiian shirts. It means drivers and bus passengers being stopped and searched and always being surrounded by police and soldiers in the streets, leaning out of big trucks or looming from helicopters with guns pointing, “preventing drug crime”.

Up in the Sierra Madre — home to the “narco-corridor” or “corridor of impunity” — are 9,000 Mexican troops. Despite their aircraft, helicopters and hunting dogs they have little success navigating the mountains; much of the narco-corridor, the main drug route from Latin America to the US, is thick jungle. The indigenous people traditionally lived in caves and El Chapo is often said to be living in one himself.

American and Mexican officials are predicting Guzmán’s imminent capture. One recently retired head of the DEA has given him until April. “We are hopeful,” said the US official in Mexico — “sooner or later”.

Ballad of a short man

Del infierno se escapa

Y se persigna en la iglesia

Y aveces las residencias aveces casa campaña los raídos y las metrallas durmiendo al piso en la cama

de techo aveces las cuevas

Joaquín el chapo le llaman

Song by The Vultures of Culicán

• • •

He escaped from hell

And crossed himself in church

Sleeping sometimes in homes

Sometimes in tents

Radios and rifles

At the foot of the bed

As a roof sometimes caves

Joaquín the Short they call him |

|

|  |