Pátzcuaro, Mexico - A lake, mountains, an ancient village, flowers, a good meal; one could be content with that.

What continues to surprise is often what we don't expect to see that, set amidst a new town or experience, can change a singular moment into a rush of memories. I suppose that is why I am compelled to travel; it always manifests into something other than the expected, becoming an amalgam of past and present.

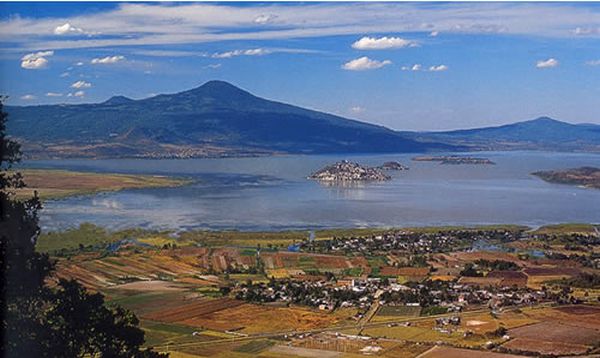

The bus from Morelia, the capital of Michoacán, takes you straight to Pátzcuaro. It is said to possess a unique beauty and charm, surrounded by slopes of volcanic mountains, pine forests, and especially rich in history, myth, and magic. But to be fair, most Mexican villages boast a rich heritage, charming squares and bustling mercados, at least one antique church and often, tales of supernatural and spiritual happenings - fantasmas or milagros that defy explanation by mere mortals.

But even the most skeptical might be curious about a village believed to be magical.

Pátzcuaro is such a town. In Mexico, the Programa Pueblos Mágicos (Magical Villages Program) promotes villages throughout the country that are deemed "magical" by possessing an abundance of cultural riches and historical relevance. However, it's more than just that. Many of the towns bestowed with this honor are known for their "magical experiences," an element unique enough to set them apart from even the most captivating of Mexican villages.

I wanted to see it all; ghosts weeping through tangled bougainvillea along ancient stone walls, the town square and its people, the local arts and crafts, but equally so, the vast lake and islands, the density of indigenous and migratory birds, and the terraced purple volcanoes. Lake Pátzcuaro teemed with songbirds and waterfowl, some migratory, but year round was a cacophony of song, shrill and melodic, often haunting, echoing across its opaque green waters. Legend said that the natives had long believed that the lake was the place where the barrier between life and death was the thinnest. Later, when I stood at its edge and looked down into the darkness, I could imagine why.

The plaza and surrounds were decidedly different. I was used to Mexican towns whose building facades were the colors of the homemade ice cream sold from carts in nearly every square; pastels of guava pink, pistachio, lilac, piña colada, pale tamarindo. Or those villages, who for centuries, splashed adaptations of primaries in turquoise and indigo blue, mustard, mango, blood red. So I didn't expect the prevailing wash of stark white paint on the centuries old buildings that stung my eyes from the reflecting sun. I averted my gaze, resting on the abundance of well-tended flowers and potted plants that the townspeople were known for. They loved their flowers and took great pride in their gardens. Whether a single window box or grand courtyard, one magnificent calla lily or a patio jungle, blossoms were as ubiquitous as cobbled streets.

Through a thin stand of ash trees my eyes settled on an old man in a wheelchair. Perhaps his brittle bones and equilibrium had adjusted to the constant jolting of rusted wheels being pushed over the undulating and unforgiving ancient stones; stones laid long before anyone here had put chair to wheels. He seemed oblivious to the lurching of his body and it reminded me of those long at sea who step onto land only to have their sea legs wobble and give way at the feel of solid ground. His pallid color, the dull gray of the chair, appeared out of sync with the colors of the Plaza Grandé and the surrounding balconies of old haciendas and colonial era mansions whose windows pulsed with begonias, hydrangeas, and leggy geraniums. He seemed like a singular vision in black and white that had been spliced into a color photograph.

Next Page ğ