|

|

|

News from Around the Americas | April 2005 News from Around the Americas | April 2005

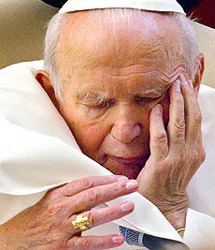

Pope John Paul II Dies at 84

Susan Hogan/Albach - The Dallas Morning News Susan Hogan/Albach - The Dallas Morning News

| Pope John Paul II

May 18, 1920 - April 2, 2005

(Photo: Patrick Hertzog / AFP) |

Pope John Paul II, who played a central role in the collapse of Communism and broke from papal tradition by preaching in more than 130 countries during his quarter-century reign, died Saturday. He was 84.

The Vatican announced his death in an email Saturday.

"The Holy Father died this evening at 9:37 p.m. (1:37 p.m. CST) in his private apartment. All the procedures outlined in the apostolic Constitution 'Universi Dominici Gregis' that was written by John Paul II on Feb. 22, 1996, have been put in motion."

Vatican protocol dictates nine days of public mourning before a secret conclave to elect his successor convenes in Rome.

The son of a Polish military officer, Karol Jozef Wojtyla become one of the most influential pontiffs in the church’s history, one whose conservative doctrinal legacy will live on for decades. In his 26 years as vicar of Christ, he appointed nearly every prelate worldwide who sits as a cardinal or bishop today.

As the leader of the world’s 1 billion Catholics, the largest religious group on earth, John Paul exerted an influence that stretched well beyond the spiritual realm, with political leaders from Mikhail Gorbachev to George W. Bush seeking his ear.

“He will go down in history as one of the most important world leaders in the second half of the 20th century,” said the Rev. Thomas Reese, editor of the Jesuit magazine America and an author of books on the Vatican.

The 264th man to sit upon St. Peter’s throne was a pope of many firsts. The Polish native was the first Slavic pope, and the first non-Italian in 455 years. He was also the first pope to pray in a Muslim mosque, one of his many efforts to build relations with non-Catholics.

A doctor of theology and philosophy, John Paul spoke seven languages when elected in 1978, and became fluent enough in several others to exchange greetings at mass audiences.

Nearly felled by an assassin in 1981, he went on to serve longer than all but three popes: Pius IX, Leo XIII and, according to church tradition, St. Peter himself.

John Paul was the most traveled pope in history. His trips included seven visits to the United States. He enjoyed wide successes as a shaper of international politics. Within a year of becoming pope, he made a dramatic return to Poland and expressed support for the anticommunist Solidarity workers movement.

“He came at a time of darkness when atheistic communism rules half of Europe and most of Asia,” said Bishop Charles Grahmann of the Catholic Diocese of Dallas. “He was the first light of emancipation for many people.”

So effective was he in undermining the communist empire that many people believe the Soviet KGB, the Soviet secret police, masterminded a 1981 assassination attempt in St. Peter’s Square. Two years after the near-fatal shooting, the pope visited his would-be assassin, Mehmet Ali Agca, in prison and forgave him for the shooting.

John Paul electrified audiences with a rock star’s charisma. He packed stadiums everywhere he went. His travels gave rise to a new word: Popemobile, the bulletproof, box-like Mercedes Benz that allowed him to stand and wave to the millions of people who lined the streets to see him.

“I am a pilgrim messenger who wants to travel the world to fulfill the mandate Christ gave to the apostles when he sent them to evangelize all men and all nations,” John Paul said during a visit to Spain in 1982.

In 1987, he came to San Antonio, his only visit to Texas.

“He always remembered those big Texas steaks we ate,” Bishop Grahmann said.

As endearing a character as he was on the world stage, John Paul ruled his church with an authoritarian hand. Shortly after his election, he began cracking down on theologians and clergy who didn’t adhere to his strict interpretation of Catholic doctrine.

The Rev. Charles Curran, a professor at Southern Methodist University, was one of the Vatican’s most public targets. He was forced from a teaching post at Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C., for questioning the church’s teachings on the use of birth control and on other sexual issues.

“There’s got to be room in the church for disagreement on specific issues,” Father Curran said. “My church is a big church, and my God is a big God.”

Throughout his papacy, John Paul remained concerned about the erosion of church teaching in modern culture. One of his most talked about encyclicals, “Veritatis splendor” (“The splendor of truth”), criticized moral relativism and dissent in the church.

John Paul championed human life and was an unyielding opponent of abortion, the death penalty and assisted suicide.

“The dignity of humanity was really his theme,” said Dr. Martin Marty, a church historian and Lutheran theologian who taught for years at the University of Chicago.

John Paul remained popular among U.S. Catholics, despite polls showing that a majority disagreed with his opposition to artificial birth control, to admitting women to the priesthood, and to allowing priests to marry.

He found firmer footing in his homeland. John Paul had lived in Poland under totalitarian regimes from ages 19 to 58, and he traveled there nine times as pope.

John Paul was elected pope on Oct. 16, 1978, at the relatively young age of 58. As archbishop of Krakow, Poland, he enjoyed a reputation as a scholar, athlete and media-savvy personality whom church leaders looked upon as a man in step with the times.

But as his papacy stretched on, he came to be viewed by some as out of step and unable to confront modern problems.

John Paul was slow to respond to the explosion of sex scandals across the United States that led to the ousting of 400 priests, 4 bishops and Boston’s cardinal last year. In 2002, he summoned American cardinals and leading bishops to Rome for a summit.

In his most forceful statement on the issue, he said there was no room in the priesthood or religious life for men who molested children. But his actions did not always fully back up those words.

Because of John Paul’s struggles to address the scandals as well as his deteriorating health, some church leaders openly called on him to resign.

“History will be critical of this pope for his failure to relinquish his office when it became obvious that he was no longer able to fulfill its demanding responsibilities,” said the Rev. Richard McBrien, a papal scholar at the University of Notre Dame.

The pope believed his growing infirmity was both a test of his faith and a chance to teach the world about the dignity of the aged and the infirm.

“I understood that I have to lead Christ’s church into this third millennium by prayer, by various programs, but I saw that this is not enough,” he said. “She must be led by suffering.”

John Paul was among the last towering figures of the generation whose moral compass was set during World War II. He made his way to the priesthood as his Jewish friends in Poland were being sent to Nazi concentration camps.

He lived to triumph over the ghosts of Hitler and of Stalin. As pope, he helped bring down the Soviet Union. And he made unprecedented overtures to Jews.

In 1979, the year after his election, he visited the death camp at Auschwitz. A few years later, he visited the Great Synagogue in Rome. Then, three years ago, 2003 he traveled to Israel, where he met Holocaust survivors at the Yad Vashem memorial.

In 1994, the Vatican established diplomatic relations with Israel. Four years later, the pope wrote a document expressing remorse for the failure of some Catholics to defend Jews against Nazi annihilation.

He also reached out to Orthodox Christians, carrying on the work begun by Pope John XXIII in the 1960s. In 2001, he visited Greece and offered a dramatic apology to Orthodox Christians for centuries of “sins of action and omission” by Catholics, including the sacking of Constantinople, a center of ancient church life.

It was one of many steps he took in hopes of healing differences that had divided Eastern and Western churches for nearly 1,000 years. Although he wasn’t warmly received, his apology and visit were widely viewed an ecumenical milestone.

On that same trip, he visited a mosque in Damascus, Syria, a historic moment in Muslim-Christian relations. He greeted Muslim leaders in Arabic before pausing for prayer.

But to some, his actions sometimes defied his words. Jews were upset by two candidates for sainthood who died at Auschwitz: Maximilian Kolbe, a Polish Franciscan monk who edited an anti-Semitic publication,and Edith Stein, a Jew-turned-Catholic.

Karol Wojtyla grew up in a small town in the Carpathian foothills, 30 miles southwest of Krakow. The town enjoyed a reputation as a regional center of literary culture, which shaped his early life.

His only sister died in infancy before he was born. His mother died of kidney failure when he was 8. Three years later, his brother, Edmund, 26, a physician, died after catching scarlet fever from a patient. A few years after that, his father, a retired military officer known for his piety, died after a prolonged illness.

“At age 20, I had already lost all of the people I loved and even the ones that I might have loved,” he once said.

In high school, he was a gifted athlete with a passion for theater and acting. But he also excelled in academics; he was class valedictorian.

During his final year, he offered the welcoming address when the archbishop of Krakow visited his school.

“In that period of my life my vocation to the priesthood had not yet matured,” John Paul wrote in his 1996 memoir, Gift and Mystery. He was never known to have had a serious romance, and later said romantic attraction was never an obstacle to his life’s calling.

He enrolled in Krakow’s Jagiellonian University in 1938, but his studies were disrupted the next year when the Nazis invaded Poland. During the war, Karol Wojtyla lived mostly on a diet of potatoes and made himself useful by working as a laborer in a quarry and a chemical plant to escape deportation to a German labor camp - or possible execution.

He was a pioneer in the underground “Rhapsodic Theater,” where he developed a reputation as one of Poland’s most gifted actors, and a writer of poetry and biblically inspired plays.

As the war went on, he witnessed attacks against every thread of the culture that he held dear. Many friends, teachers and priests were slaughtered. He said that living through the horror deepened his faith and fostered a growing desire to become a priest.

But in Gift and Mystery, John Paul said the greatest influence on his decision was witnessing his father’s prayerful life and self-sacrifice.

“Sometimes I would wake up during the night and find my father on his knees, just as I would always see him kneeling in the parish church,” John Paul wrote. “We never spoke about a vocation to the priesthood, but his example was in a way my first seminary.”

In 1942, he entered an underground seminary forbidden by the Nazis.

He was ordained a priest on Nov. 1, 1946, even as Josef Stalin’s forces imposed an official postwar atheism on his country. After ordination, he studied in Rome and at the University of Krakow. In 1956, he was appointed a professor of ethics at the University of Lublin in eastern Poland, the only Catholic university behind the Iron Curtain. He was soon publishing articles and books.

The Vatican saw his leadership potential. At age 38, he became Poland’s youngest bishop, when he was appointed the auxiliary bishop of Krakow in 1958. Five years later, he was named an archbishop. In 1967, at age 47, he became a cardinal.

He was elected pope in 1978 after the princes of the church deadlocked over two Italian candidates. Because John Paul I had died after only 33 days in office, the cardinal electors sought a young, vigorous successor. One of the shortest papacies in history was to be followed by one of the longest. John Paul adopted his papal name in honor of his predecessor, the first double-named pope in history. The name honored Pope John XXIII and Pope Paul VI, who’d preceded John Paul I.

Almost immediately, John Paul II became a familiar face worldwide, moreso than other popes because he embraced television and the world of media technology. Photos of him hiking and skiing made the papacy less distant.

During his time in office, the church grew from 600 million to more than 1 billion members.

His willingness to stand up to despots of all stripes made him popular among people who might otherwise not have paid much attention to the leader of the world’s Catholics.

John Paul decried the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. But he did not support the U.S. military response in Afghanistan or the war on Iraq.

“How greatly today’s world needs God’s mercy,” he once said.

In his final years, failing health forced him to trim a rigorous schedule. He canceled trips and curtailed his work hours. Sometimes, others would deliver sermons he’d prepared.

John Paul’s death leaves large parts of the church firmly committed to his interpretation of Catholic doctrine. But many others - particularly in the American church - are divided between a desire for church reform and a strict adherence to church teachings.

Some Catholics, particularly Americans, disagreed with the pope’s approach and were inclined to see religious and moral truths as matters to be debated and discovered, not accepted on papal authority.

“He presented was a very good challenge to the relativism that is so common in American society and American culture,” Father Reese said.

“On the other hand, he also made it difficult for theologians and moralists to discuss certain issues.

“In his silencing and condemning, he alienated many theologians.”

By the late 1990s, age and illness were taking their toll on the once-vigorous athlete. In 1992, a precancerous tumor was removed from his abdomen. In 1999, he fell and hit his head. Parkinson’s disease caused his hands to tremble and his speech to be slurred. Over the years, he endured six surgeries, including a hip replacement.

During a four-day trip to Krakow in August 2002, John Paul told 2 million worshipers at an open-air Mass that it might be his last trip home. He was right.

In a rare departure, the pope spoke openly about his health problems. He asked his fellow Poles to pray for him as long as he lived, and after he died.

In bidding the crowd farewell, he said: “I would like to add, until the next time, but that is entirely in the hands of God.”

His audience responded by singing out the verses of a Polish folk song, “May he live 100 years.”

Staff writers George Rodrigue and Jeffrey Weiss contributed to this report. |

| |

|