|

|

|

News from Around the Americas | July 2005 News from Around the Americas | July 2005

Collectors Snapping Up Racially Controversial Mexican Stamps

Richard Marosi - LATimes Richard Marosi - LATimes

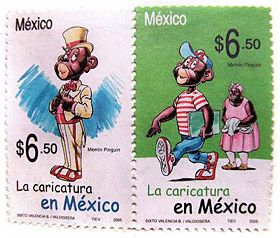

| | A set of Mexican postage stamps featuring the black comic book figure Memin Pinguin has sparked off a fresh row with the United States where anti-racism activists want them banned. |

The racist past came alive for African American memorabilia collector Brian Breye of Los Angeles when Mexico issued a commemorative stamp set celebrating the comic book character Memin Pinguin, a wide-eyed black boy with exaggerated thick lips.

Breye was so offended that he now wants to buy his own set of the stamps to preserve a disturbing page of history, part of a multifaceted purchasing frenzy for the images that have sparked a diplomatic tiff and highlighted the immense cultural divide between the U.S. and Mexico over racial issues.

"Here we go again. Here we go with race-baiting another group of people trying to place us at the bottom of the totem pole," Breye said.

About 700,000 stamps sold out within days at post offices across Mexico, where people often waited in line for hours.

At Internet auction sites like EBay, the price for a sheet of 50 stamps — with a face value of 6½ pesos each, or about 60 cents — had reached $200, though it has dropped in recent days. The sheet sold for about $30 at the post offices.

The stamps are part of a series of limited editions celebrating comic book characters, and Mexican officials say they have no plans to issue more of the Memin Pinguin stamps.

Collectors' motivations vary. Many are profit-minded investors hoping the controversy pushes up values.

But strong emotional feelings, ranging from nostalgia to outrage, are also motivating factors, reflecting deep differences in the way Mexicans and African Americans perceive Memin Pinguin.

Mexicans are snapping up the stamps because of fondness for a beloved comic character whose popularity peaked 40 years ago and is surging again thanks to the controversy. Mexican President Vicente Fox defended the stamps, calling Memin Pinguin a cherished figure. Others said the stamps reminded them of their youth.

"I read it as a child," said Miguel Alarcon, a 35-year-old graduate student who bought the stamps at a post office in Sinaloa. "I want to keep these stamps as a memory."

For many American collectors, the stamps prompt disgust, but they say possessing them is a way to preserve a bit of racist history. Breye plans to buy a set and display them with his collection of Mammy cookie jars, Negro-head salt and pepper shakers, and other racist memorabilia for sale at his Leimert Park store.

Collections of racially offensive images are not uncommon in African American homes. The Mexican stamps are a modern example of images that haunted blacks through slavery, the Jim Crow years and the civil rights era. Such collections — often prominently displayed in living rooms — raise youngsters' awareness of past indignities, say some collectors.

David Pilgrim, curator of the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia in Big Rapids, Mich., said he purchased two sets of stamps for the museum, where the 5,000 items — everything from Ku Klux Klan robes to Aunt Jemima advertisements — already include Memin Pinguin comic books and T-shirts.

"Our mission is to use items of intolerance to teach tolerance. Racism has to be viewed openly, honestly and directly," Pilgrim said.

The Memin Pinguin character was created in 1947 by an impoverished aspiring singer, Yolanda Vargas Dulche, who was inspired by the black children she saw during a trip to Cuba.

She said she "made Memin black because the children of color fascinated me, with their faces so open," according to a quote attributed to her by her son, Manelick de la Parra.

Memin Pinguin, the mischievous son of a poor washerwoman — a chubby, Mammy-like character — hangs out with a group of white kids. They often taunt him and ridicule his antics, but their short friend teaches them lessons, De la Parra said.

"People can't say it's racist. He suffers because they make fun of his color, but he shows that he's like anyone else," De la Parra said in a telephone interview.

De la Parra said the comic book was once distributed in other Latin American countries, Indonesia and Hong Kong. Schoolchildren in the Philippines, he said, were once obligated to read it because officials believed it promoted family values.

African Americans say it only perpetuates negative racial stereotypes. Where Mexicans see a cute and adorable child, blacks see an ignorant, anatomically exaggerated fool.

In recently released comic book issues, Memin Pinguin smashes a rock over a man's head, knocking him out. He swats a child for a perceived insult to his mother. But in general, he exudes a happy-go-lucky attitude that African Americans say is typical of caricatured images of black people.

"He's a typical Sambo character," said Sidney Lemelle, a professor of black studies at Pomona College who has studied Afro-Mexican history.

Criticism from African Americans — among them the Revs. Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton — has been met with defiance from Mexican officials, including Fox, who refused their requests to recall the stamps.

The controversy has baffled ordinary Mexicans. On the same day last week that three African American activists in Los Angeles were arrested during a protest outside the Mexican Consulate, Tijuana residents were eager to buy the latest issue of the comic at newsstands downtown.

Haide Serrano, a Tijuana print store owner, missed out on the stamps, which sold out in five hours Monday, so she bought the comic book for her son. Told that African Americans consider the character's exaggerated features demeaning, Serrano, gazing at the image, disagreed.

"It is not racist. He's funny," she said. "It's a Mexican tradition. We don't have anything against people of color."

Some Americans agree. Janelle Norris, a 40-year-old white woman from Austin, Texas, said she bought a set of stamps on EBay because she couldn't believe such a stir for "something so innocent." The character reminded her of her own youth in Kansas reading Sambo books, she said.

Norris wants to put the stamps in her granddaughter's safe deposit box, so she can someday tell her how "stupid people were."

"Maybe 20 years from now, people would realize that this is not racist," Norris said. "It's just celebrating a comic book character from the '40s."

Such varied motivations are not surprising to Pilgrim, the curator. He said black memorabilia draws many types of buyers, from racists to regular stamp collectors to nostalgia fans.

Speculators — the largest group — seek profits. Liberators, as he calls them, purchase items to destroy them because they don't want anyone to see them. Parents buy them to give their children a sense of history.

One EBay buyer said he bought the stamps so his children realize "they must always work through the drama life has."

"I've only bid on the stamps to show my kids that no matter how far society believes it has come, there are always thoughtless acts," the buyer said.

Some racist memorabilia collectors will be sitting out the auctions.

Avery Clayton, chief executive officer of the Western States Black Research and Educational Center in Los Angeles, said the stamps are too hurtful to be instructive, particularly at a time when black-Latino relations in Los Angeles are strained.

While he believes owning racist items can take away their "racial sting," he said the stamps serve no purpose other than to inflame tensions.

"This is a racial stereotype that harks back to a time when depictions of blacks were done to be deliberately vulgar. It's an insult," Clayton said. "They're saying, 'We don't give a damn about how you feel.' I think it's horrible." |

| |

|