|

|

|

Business News | April 2006 Business News | April 2006

Mexico's Stubborn Lack of Choices

Marla Dickerson - LATimes Marla Dickerson - LATimes

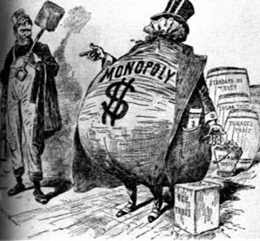

| | Oligopolies abound, leaving consumers with few options and high prices. The scarcity of competition is seen as an economic impediment. |

Mexico City — When voters tossed out the ruling party in national elections six years ago, they gave a resounding no to a continuation of a 71-year political monopoly.

But in another arena in which they can wield their votes — with their pocketbooks — Mexicans continue to be frustrated by a lack of true choice.

Placing a call? For the minority of Mexicans who can afford a phone, their service comes from a telecom group that controls 94% of land lines and 80% of cellular service, charging rates that are among the highest in the world.

Watching TV? Two behemoths own 94% of Mexico's television stations, and recent legislation probably only served to strengthen their grip.

Buying a beer? Whatever the brand, chances are it was brewed by one of two companies whose combined share of the market tops 99%.

With a presidential election coming in July, Mexicans are debating the merits of three major candidates and a host of minor ones vying to succeed Vicente Fox, who is prevented by law from seeking another term.

But analysts and scholars of Mexican business say the country's oligopolies and monopolies, in both the private and public sectors, may prove tougher to dislodge than the Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, which for decades ran things until Fox of the National Action Party was elected president in 2000.

"Mexico has been a paradise to create and sustain unhealthy monopoly practices," said Mexico City political scientist Ricardo Raphael, a researcher at the Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education, who blames weak antitrust legislation and Mexico's long history of crony capitalism for concentrating power in relatively few hands.

Economists say business monopolies have saddled Mexican consumers with high prices, slowed the country's economic growth and exacerbated the divide between rich and poor.

Nearly half of Mexico's 106 million people live in poverty. Yet it has more billionaires than Switzerland — 10 last year — according to Forbes magazine's latest list of the world's richest people. Most of them built their fortunes in Mexican industries that have little or no competition.

And the power brokers may only be strengthening their hands these days. Mexico's business barons have been aggressively defending their turf, rivaling the nation's presidential contenders for headlines.

Mexico's media leviathan, Grupo Televisa, and runner-up TV Azteca, which combined garner nearly every peso spent on television advertising in the country, pushed hard to win approval of legislation last month that granted them additional broadcasting spectrum to help them convert to digital services. The rub, critics note: Nothing in the legislation expressly requires that they pay for it.

Televisa and TV Azteca used their news broadcasts to stump for the law. Mexico's Congress approved the measure handily amid widespread public protests and allegations that lawmakers consented in exchange for bribes and positive news coverage of their parties' presidential candidates during the campaign.

The broadcasters and legislators denied any backroom deals, but many Mexicans weren't convinced. An angry mob roughed up a key Senate leader after the vote. Critics said the law amounted to a giveaway of public assets worth billions of dollars that also would block new players from the market.

Lawmakers caved in to "the vested interests that are the main obstacles to modernization of the Mexican economy," said Mexico City-based political scientist and newspaper columnist Denise Dresser.

Televisa and TV Azteca "used a public concession to defend a private economic interest," Dresser said. "You basically have an economic monopoly determining the rules of the game."

Moguls in other sectors are flexing their political muscle as well.

Mexican trade officials recently succeeded in opening the U.S. market to more imports of Mexican cement, a move that could lower costs for American home builders. But the government hasn't been as considerate of consumers in its own country, who have long complained of inflated prices. At the behest of Cemex, which controls more than half the market here, Mexican officials last year turned away a cargo ship loaded with 26,000 tons of Russian cement.

In the beer industry, Grupo Modelo and Cerveceria Cuauhtemoc Moctezuma, whose brands dominate the Mexican market, supported a new environmental tax on nonreturnable beer bottles that falls heaviest on imports. Importers lack the collection network of domestic giants and therefore sell such nonreturnable bottles.

Attempts by Mexico's Federal Competition Commission to put teeth into the nation's antitrust laws have run into a buzz saw of opposition from business leaders.

Topping the agency's wish list is having the ability to break up companies whose market power is deemed excessive. It's a standard tool provided to regulators in the United States and other developed economies, but one that doesn't exist in Mexico. Corporate titans here are working furiously behind the scenes to keep it that way.

Eduardo Perez Motta, president of the competition commission, vented his frustration at a recent news conference.

"It's incredible that these [businessmen] are fighting to maintain their privileges," Motta said. "They don't have the public justification to do it, but that's what they are doing … [using] all manner of sophistry, legal and otherwise."

Mexico's oligopolies have their roots in protectionist philosophy that shaped the nation's industrial policy after World War II. The goal was to reduce reliance on imports by building up strong domestic players in key sectors of the economy. Through the years, the PRI-controlled government kept a firm hand in the economy through state-owned companies and chummy relationships with some pro-regime entrepreneurs, who were sheltered from competition.

Televisa, for example, functioned for decades as a de facto government mouthpiece in exchange for a virtual monopoly on TV broadcasting. The late Emilio Azcarraga Milmo, who headed the company, once publicly declared himself "a soldier of the president and at the service of the PRI" and reportedly pledged more than $50 million at a party fundraiser to show his gratitude for his company's privileged status.

A devastating financial crisis in the 1980s forced Mexico to open itself to more foreign investment and to unload a spate of state-owned firms. But experts say Mexico's privatizations in some respects saddled the nation with the worst of all worlds: Instead of breaking up public enterprises to spark competition, the government simply transferred them to new owners.

"They replaced public monopolies with private ones," said Celso Garrido, an economist at the Autonomous Metropolitan University in Mexico City.

The best known of these transactions was the 1990 sale of state-owned telephone company Telmex to a consortium led by Mexican entrepreneur Carlos Slim, who used the company as a springboard to expand into mobile phone service and telecommunications ventures throughout Latin America. Forbes recently estimated Slim's fortune at $30 billion, making him the world's third-richest man, behind Bill Gates and Warren Buffett.

Slim has shown a talent for spotting undervalued assets. But critics say hard-nosed tactics have helped him retain a lock on the lucrative Mexican telecom market. Telmex and America Movil, Slim's cellphone company, last year garnered more than 60% of their combined $31 billion in revenue from Mexican consumers.

The office of the U.S. trade representative repeatedly has criticized Telmex's use of Mexico's ponderous legal system to block efforts by Mexican regulators to spur competition. Mexico's central bank governor, Guillermo Ortiz, recently blasted Slim's telecom companies for hampering the nation's competitiveness by charging Mexican businesses and individuals some of the highest rates on the planet.

Slim strongly denied Ortiz's assertions and blamed government monopolies and inefficiency for Mexico's woes. It was an unusual and highly publicized spitting match whose U.S. equivalent would see Microsoft Corp. founder Gates exchanging insults with Federal Reserve Chairman Ben S. Bernanke.

Ortiz also laid into Mexico's commercial banking system, which is dominated by a handful of large institutions, accusing them of stingy lending practices, outsized fees and inflated credit card interest rates that can top 40% a year.

Analysts say a lack of credit is one of the biggest factors retarding economic growth in Mexico, where the vast majority of residents don't have bank accounts and most small entrepreneurs can't get a loan.

"The banking system mostly serves the interest of big corporations," said Alfredo Coutino, senior economist at West Chester, Pa.-based Moody's Economy.com.

Bully pulpits are one of the few reliable tools that Mexican officials have at their disposal. Regulators have scored a few victories, such as opening Mexico's airline industry to discount carriers. And the nation's Congress may well approve some changes to antitrust laws this year. But experts say the reforms will fall short of what officials say they need to foster true competition.

Mexico's public monopolies may be even harder to crack.

Debt-strapped oil giant Pemex needs billions of dollars in new investment to shore up Mexico's rapidly declining petroleum reserves. But the nation's constitution prevents any equity investments in the state-owned firm by foreigners, inhibiting Mexico's ability to team with major oil companies to find and extract more crude.

Similar rules are burdening Mexico's publicly owned electricity sector, whose unreliable service and high rates put yet another damper on economic growth.

But analysts said many Mexicans remained suspicious of further sell-offs of public assets, given the experience of companies such as Telmex, whose sale transformed buyer Slim into a billionaire in a country where 60% of Mexican households still lack a telephone.

"There have been a lot of abuses in the past," economist Coutino said. Government officials "don't have the ability to convince society about the benefits."

Kings of their Markets - When it comes to competition, less is more for Mexico's oligopolies, which dominate key sectors of the economy.

Market share of companies in selected industries

Broadcasting: Grupo Televisa -- 56%*, TV Azteca -- 38%*

Cement: Cemex -- 54%, Holcim Apasco -- 23%

Beer: Grupo Modelo -- 57%, Cerveceria Cuauhtemoc Moctezuma-- 43%

Tortillas/corn meal: Gruma -- 73%, Minsa -- 15%

*Percentage of television stations owned

Sources: Company reports, Times research |

| |

|