|

|

|

News Around the Republic of Mexico | July 2006 News Around the Republic of Mexico | July 2006

The Migrant's Saint: Toribio Romo is a Favorite of Mexicans Crossing the Border

Alfredo Corchado - Dallas Morning News Alfredo Corchado - Dallas Morning News

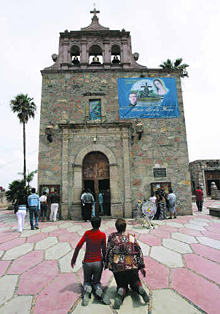

| | The Shrine of St. Toribio, in Santa Ana de Guadalupe, draws pilgrims from throughout Mexico. (Erich Schlegel/DMN) |

Santa Ana de Guadalupe, Mexico – As the United States calls out the National Guard and prepares to build new fences along the border, some migrants in this deeply Catholic area are seeking assistance – but not from some ordinary coyote or guide.

They're turning to a saint.

His name is Toribio Romo González, a priest whose rise to sainthood began in the 1920s, after he was killed during a Christian uprising in this central-coastal state of Jalisco.

To many, he's known as a patron of migrants – a figure who, legend has it, has led to safety many who have braved the hazards of border crossings.

The popularity of the priest has soared since he died in 1928. Many Mexicans who have headed north or returned home tell inspirational stories about being spared through St. Toribio's intervention.

Luciano González López, 45, who returned not long ago to his hometown of Teocatilche from Denver, tells such a tale.

Last year, he said, he and two other men were on their way to Colorado in search of work, when they got lost in the smoldering Arizona desert.

They walked for nearly two days without water, he said, when suddenly they saw a shadowy figure standing next to what looked like an ocean.

"It wasn't an ocean," he said. (They were, after all, in the middle of the Sonoran Desert.) "But the sight of this man next to an ocean gave us enough hope to follow him out."

With tears rolling down his cheek as his son Benito put an arm around him, he went on:

"When I told my wife back in Mexico, she responded: 'It was St. Toribio, the migrant-smuggling saint, leading you to safety. I had been praying to him for your well-being.'"

"Suddenly, everything made sense. It was a santo coyote who saved us."

Such stories – and such faith – have made St. Toribio's hometown a thriving destination for tourists and religious pilgrims. A few years ago, The New York Times described Santa Ana de Guadalupe as "once a dying village of 400 cattle farmers." Today, the remote town attracts hundreds, sometimes thousands, of visitors each week. Many are Mexicans living in the U.S. who are home for a visit. Many are migrants about to head north.

A new, larger church is under construction. Street vendors do a brisk trade hawking everything from religious medals to pirated CDs, including one compilation of Mexican folk songs heralding St. Toribio's works.

"He was killed years ago, but his soul is still very much with us today," said Juana Romo, a 79-year-old vendor who identified herself as a cousin of the dead saint.

Father Romo was killed on Feb. 25, 1928, by Mexican soldiers during the Cristero War, a popular uprising against the anti-clerical provisions of the 1917 Mexican Constitution. In 2000, Pope John Paul II canonized him and 24 other Catholics martyred in the war.

"He was a priest with a sensitive heart, an ardent homilist," according to the Vatican's official Web site. "A lover of the Eucharist, he often prayed, 'Lord, do not leave me, nor permit a day of my life to pass, without my saying the Mass, without receiving your embrace in Communion.' "

Some Mexicans said even more migrants will seek the protection of St. Toribio, as Americans step up efforts to curb illegal border crossings.

Yet, few people here expect the border measures – from more troops to higher walls to costly night-vision cameras – to much discourage illegal migration, despite its risks. Last year, almost 500 people, most of them Mexicans, died trying to reach U.S. soil.

And so, many people from across Mexico are flocking to this region, known as Los Altos de Jalisco, in search of a guide with a reputation for divine powers. Many maintain that only a miracle can help them overcome the growing array of obstacles.

"The number of migrants coming here in search of miracles is growing and will only get bigger," said the Rev. Gabriel González Pérez, parish priest of the small chapel where the remains of St. Toribio are buried.

"Father Toribio's philosophy was that hunger knows no border. That's why many migrants come here and pray to him. And then they ask us to bless key chains or pictures of Father Toribio before they put them around their necks."

"They're putting their faith and lives in his hands."

According to legend, it was in the late 1970s that migrants began telling stories about St. Toribio's coming to their rescue.

One such tale, from the 1990s, is about a man named Jesús Buendía Gaytán. He reported that he'd been walking several days in the desert, barely alive, when he saw a thin young man with white skin and piercing blue eyes. The man offered him food and water, spoke to him in Spanish, and even gave him a few dollars.

The young man had one request: "When you finally get a job and money, look for me in Santa Ana de Guadalupe, Jalisco. Ask for Toribio Romo."

Years later, the story goes, Seńor Gaytán visited Santa Ana de Guadalupe, in search of his Good Samaritan. He was said to be dumbfounded, on seeing a photo of St. Toribio, to recognize the face of his coyote.

The Catholic Church does not officially confirm such miracles by the saint along the border. Nonetheless, said Father González, some dioceses in Mexico and the U.S. are lobbying to have Toribio declared the official patron saint of migrants.

Among the visitors to Santa Ana de Guadalupe on a recent Saturday was Alberto González, 23. He had returned to Mexico from North Texas, where he'd worked for three years in construction.

Outside the chapel, the family munched on corn on the cob and listened as a local band jammed.

Mr. González said his thoughts were already on his next journey northward. He plans a return to the Dallas area later this year.

"For sure, it'll be the most difficult crossing," he said. "That's why I'm here – asking Father Toribio to guide me across, to perform another miracle."

Email acorchado@dallasnews.com |

| |

|