|

|

|

Technology News | August 2006 Technology News | August 2006

Pull the Plug

Aviel Rubin - Forbes Magazine Aviel Rubin - Forbes Magazine

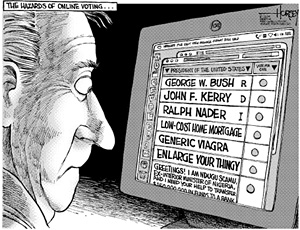

| | (David Horsey/Seattle Post-Intelligencer) |

You don't like hanging chads? Get ready for cheating chips and doctored drives.

I am a computer scientist. I own seven Macintosh computers, one Windows machine and a Palm Treo 700p with a GPS unit, and I chose my car (Infiniti M35x) because it had the most gadgets of any vehicle in its class. My 7-year-old daughter uses email. So why am I advocating the use of 17th-century technology for voting in the 21st century-as one of my critics puts it?

The 2000 debacle in Florida spurred a rush to computerize voting. In 2002 Congress passed the Help America Vote Act, which handed out $2.6 billion to spend on voting machines. Most of that cash was used to acquire Direct Recording Electronic voting machines.

Yet while computers are very proficient at counting, displaying choices and producing records, we should not rely on computers alone to count votes in public elections. The people who program them make mistakes, and, safeguards aside, they are more vulnerable to manipulation than most people realize. Even an event as common as a power glitch could cause a hard disk to fail or a magnetic card that holds votes to permanently lose its data. The only remedy then: Ask voters to come back to the polls. In a 2003 election in Boone County, Ind., DREs recorded 144,000 votes in one precinct populated with fewer than 6,000 registered voters. Though election officials caught the error, it's easy to imagine a scenario where such mistakes would go undetected until after a victor has been declared.

Consider one simple mode of attack that has already proved effective on a widely used DRE, the Accuvote made by Diebold (nyse: DBD - news - people ). It's called overwriting the boot loader, the software that runs first when the machine is booted up. The boot loader controls which operating system loads, so it is the most security-critical piece of the machine. In overwriting it an attacker can, for example, make the machine count every fifth Republican vote as a Democratic vote, swap the vote outcome at the end of the election or produce a completely fabricated result. To stage this attack, a night janitor at the polling place would need only a few seconds' worth of access to the computer's memory card slot.

Further, an attacker can modify what's known as the ballot definition file on the memory card. The outcome: Votes for two candidates for a particular office are swapped. This attack works by programming the software to recognize the precinct number where the machine is situated. If the attack code limits its execution to precincts that are statistically close but still favor a particular party, it goes unnoticed.

One might argue that one way to prevent this attack is to randomize the precinct numbers inside the software. But that's an argument made in hindsight. If the defense against the attack is not built into the voting system, the attack will work, and there are virtually limitless ways to attack a system. And let's not count on hiring 24-hour security guards toprotect voting machines.

DREs have a transparency problem: You can't easily discover if they'vebeen tinkered with. It's one thing to suspect that officials have miscounted hanging chads but something else entirely for people to wonder whether a corrupt programmer working behind the scenes has rigged a computer to help his side.

My ideal system isn't entirely Luddite. It physically separates the candidate selection process from vote casting. Voters make their selections on a touchscreen machine, but the machine does not tabulate votes. It simply prints out paper ballots with the voters' choices marked. The voters review the paper ballots to make sure the votes have been properly recorded. Then the votes are counted; one way is by running them through an optical scanner. After the polls close, some number of precincts are chosen at random, and the ballots are hand counted and compared with the optical scan totals to make sure they are accurate. The beauty of this system is that it leaves a tangible audit trail. Even the designer of the system cannot cheat if the voters check the printed ballots and if the optical scanners are audited.

Aviel Rubin, professor of computer science at Johns Hopkins University and author of Brave New Ballot: The Battle To Safeguard Democracy In The Age Of Electronic Voting. |

| |

|