|

|

|

News Around the Republic of Mexico | January 2007 News Around the Republic of Mexico | January 2007

Rough Waters: Billings Couple Loses Sailboat Off Coast of Mexico

Lorna Thackeray - Billings Gazette Lorna Thackeray - Billings Gazette

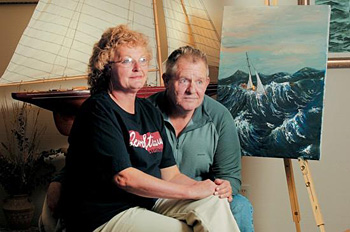

| | Dennis and Leslie Downing reflect on their shipwreck off the coast of Mexico in November. Dennis painted the picture at right before the trip, but said the seas they encountered were just as the painting shows. (David Grubbs/Gazette) |

Fear gripped Leslie Downing every time the swells threw her sailboat's bow 30 feet above the churning waters off the Mexican coast and slapped it down again.

A pre-Thanksgiving dream voyage the Billings woman and her husband, Dennis, were making from San Diego to Cabo San Lucas at the tip of Mexico's Baja Peninsula had turned into their worst nightmare.

Waves 20 feet high washed over the deck of the 41-foot sloop she and her husband had named Christabella. Only a tether attached to his life vest kept Dennis from falling into the storm-roiled Pacific Ocean.

Then the boat's 9,000-pound keel pounded an uncharted reef 300 yards from shore. "I'll never forget that sound, the feeling you get," she said. "I tell you what, I did a lot of praying."

The couple had been fighting the storm for eight hours and was nearly spent.

"You hear about people becoming so exhausted they just give up," she said. "That's about where we were."

"The adrenaline was way gone," Dennis said.

The engine had blown and the mainsail had crashed to the deck from its 56-foot mast as a chubasco - a sudden, violent tropical storm - overtook them. The forecast before they had left Ensenada, Mexico, the day before called for smooth sailing and 9 to 10 mph winds for the next 10 days.

The chubasco formed about 10 miles out at sea. To avoid the worst of it, they had moved to within five miles of shore. Even there, winds were stirring 15-foot waves.

Dennis, who had taken advanced training at a top sailing school in San Francisco, had learned what to do in all kinds of emergencies. His chart showed a bay not far from their position and he maneuvered the craft into waters where he believed they could ride out the storm.

He hadn't counted on the unmarked reef - or the two rocks "the size of a house" that suddenly rose from the crashing swells behind them. The waves were dragging the sea anchor, and with it the Christabella, toward those rocks.

"My insides got all hot and liquidy," Leslie said. "I believed we were going to die."

Dennis had her get on the radio and issue a "pan" call.

"That's a step lower than mayday, but it means you've got serious problems and need help," Dennis said.

They fired their emergency flares, trying to attract attention in the small village they could see on shore, but the flare, "about as bright as a match stick," made a disappointing arc into the ocean. Then they tried the bullhorn, broadcasting their cries for help at ear-damaging volume. Nobody heard them over the crashing waves.

Finally, they decided the time had come to set off their emergency locator signal.

Leslie, who doesn't speak much Spanish, eventually got an answer on the radio. Almost giddy with relief, she told Dennis the Mexican Navy was on its way and would be there in 10 minutes.

"The Mexican Navy turned out to be three fishermen in a 15-foot panga with a 75-horsepower engine," Dennis said with a laugh at home in Billings. A panga is a small open boat, Dennis said.

The fishermen tried to tow the crippled sloop, but their own craft was too small. They told the Downings to jump in the water and that they would pull them out. Leslie balked.

"There was no way I could make myself jump," she said. "The wind was blowing and the water was churning and I was like, 'Are you crazy?' "

The fishermen, battered by the waves and the larger sailboat, maneuvered alongside. As Leslie was almost aboard the panga, a swell knocked her inside and on top of the fishermen. Dennis was able to just step aboard as the fishing boat rose on the breaking wave.

"Those Mexicans were heroic," Dennis said.

At great risk to themselves, people in the fishing village tried to free the sailboat, but she sank in 30 feet of water, her mast the only thing visible in the bay. A local diver tried to retrieve some of the Downings' belongings but was interrupted by the arrival of great white sharks. He slowly made his way back to shore, avoiding paddling or splashing that the sharks could mistake for food noises.

As traumatic as the sinking was, the Downings say that overall, they had a good experience.

"We had thought there was no more kindness left," Leslie said. "What we have found is there is kindness out there in smaller pockets."

From the minute the fishermen arrived, the Downings received nothing but kindness and sympathy, they said. Everyone - from the poor people in the fishing village to strangers willing to lend credit cards - rekindled their faith in the human race.

The matriarch of the village of about 300 - a woman named Adella - offered them a fishing cabana and brought them fried clams with rice and corn. The cabana was a cinderblock structure with a concrete floor and bunk beds, "but it looked like heaven to us," Leslie said.

They were safe on dry land but had no money, passports or clothing, other than the tattered togs they were wearing when Christabella foundered. The villagers brought them some clothing to supplement the diesel-saturated items the fisherman had retrieved from the sunken boat.

A group of sport fishermen from Bakersfield, Calif., lent them $200 and gave them food. One of the native fishermen offered to give them $200 he had saved.

"Nobody would take money for anything," Dennis said.

"We asked Adella how much we owed and if there was anything that she needed that we could send," Leslie said. "All she kept saying is that she was just glad we were safe. She told us to send her a picture of us with our family and friends smiling. She said nothing else matters."

Once the Downings decided their boat would not be salvageable, they signed a legal document turning it over to the town for whatever the fishermen could retrieve.

Then they had to find a way back home.

Adella and her husband drove them up the peninsula to Ensenada, where they could catch a bus to Tijuana.

"We looked like a couple of street people with our borrowed clothes and what was left of our belongings in two plastic garbage bags," Leslie said.

At Tijuana, the only document they could show was a police report of the boating accident. Sympathetic border guards allowed them to cross into the United States.

They took a trolley to the train depot in San Diego, but were unable to get on a train that would have taken them to Santa Maria, where Dennis' sister lived and where they had left their car.

A stranger at the station collected their belongings, got them a taxi and called a hotel. After paying the hotel bill, they had $7 left, and had a hot dog at a 7-Eleven.

Broke and bedraggled, they got a taxi to a Wells Fargo Bank in San Diego. Looking as they did, and with no documentation, the Downings didn't know how they would be received.

They showed a bank officer the police report and told their story. She cancelled her appointments for the day and set to work helping the Downings. Before they left the bank, they had $5,000 from their Wells Fargo account in Billings in their hands.

The bank officer advised them to go to the California Department of Motor Vehicles and see if the department could get them copies of their Montana driver's licenses so they would have some identification.

They took a taxi to the DMV. None of the cab drivers they rode with that day charged them, they said. A clerk at the DMV told them he couldn't help, but a well-dressed man mingling among the customers heard their story and asked them to step into his office. Dennis said the man turned out to be the DMV director. He got the DMV in Montana to fax copies of the driver's licenses to California.

From there, the Downings caught a train to Santa Maria. It was 1 a.m. when a bus dropped them off at a hotel. Although they had cash, the desk clerk said she couldn't let them in unless they had a valid credit card.

They were sitting in front of the hotel when a car pulled up. The driver, a tourist from Scotland, took them to the hotel and put their room on his credit card. The next morning Dennis paid the bill in cash and they were on their way.

His sister spent Thanksgiving in Arizona, but left the Downings a key and the run of her house. After purchasing the necessities and regrouping, they drove to San Francisco to have Thanksgiving with Leslie's brother. He gave them some luggage.

The Downings made it home to Billings on Nov. 26. Leslie, a nurse, went back to work Dec. 11.

They lost the sloop they had bought for $20,000 and spent another $20,000 and months of labor refitting. Their homeowner's insurance has agreed to cover personal property that went down with the boat, including a computer, cameras and telephones.

The Downings put together a Christmas box for Adella and the villagers, including a VHF radio for communicating with vessels on the ocean, boxes of chocolates, and clothing, pens, pencils, crayons, paper and coloring books for the children.

Despite disastrous results on their first attempt at an extended ocean journey, their fascination with a lifestyle that began six years ago when they traded a horse trailer for their first sailboat has not diminished.

Leslie, who said she could barely swim when they got their first boat, was hooked her third day of a trial run in Puget Sound.

"I loved everything about it," she said, and now considers herself "a pretty good first mate."

Not even two months after the Christabella sank, they are ready to go again. Dennis, a retired pharmaceutical representative, went to Puerto Vallarta to check out a 45-foot sailboat for sale there. If it doesn't seem right, there's another likely prospect moored in Tobago in the West Indies.

Dennis would like to live on a new boat for the winter. Leslie wants to sail it through the Panama Canal.

Contact Lorna Thackeray at lthackeray@billingsgazette.com or 657-1314. |

| |

|