|

|

|

News from Around Banderas Bay | March 2007 News from Around Banderas Bay | March 2007

Popularity, Precedent Could Keep Dog Free

Lee Catterall - starbulletin.com Lee Catterall - starbulletin.com

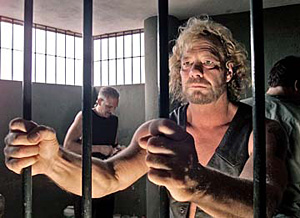

| | Bounty hunter Duane "Dog" Chapman holds the steel bars of a jail cell in Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, as his associate Tim Chapman, left, and freelance television producer Jeff Sells pass the time, in this photo taken June 19, 2003. (Associated Press) |

Revered at home for his capture in Puerto Vallarta of millionaire serial rapist Andrew Luster, Hawaii-based bounty hunter Duane "Dog" Chapman might be a bitter reminder to Mexican law enforcement of a controversy concerning a 1990 abduction south of the border.

Mexico was angered two years later when the U.S. Supreme Court approved of the Drug Enforcement Agency's hiring of several Mexicans to capture a doctor in Guadalajara to stand trial in the United States in the slaying of a DEA agent. The first Bush administration promised not to engage in transborder abductions again.

Although the two governments also agreed to recognize transborder captures by bounty hunters as extraditable offenses, the proviso never was incorporated into extradition treaties.

Chapman is charged in Mexico with deprivation of Luster's liberty, an offense for which he could be extradited. However, U.S. judges have differed in civil and criminal cases about whether abductions under such circumstances are extraditable.

Public opinion is not supposed to count for much in a court of law, but it might be critical in the battle over Mexico's attempt to extradite Hawaii bounty hunter Duane "Dog" Chapman for his capture of Max Factor heir and sexual assailant Andrew Luster.

If the issue of Chapman's extradition comes to U.S. federal court, a judge could exercise wide discretion on how to rule, because the issue might fall outside the extradition treaty between the United States and Mexico. For now, the case against Chapman is pending in the Mexican court system. Public pressure could come into play in either country -- Chapman's charisma has captivated millions of viewers of his Hawaii-based hit television show, "Dog the Bounty Hunter," which in turn has fueled his notoriety.

A state House resolution on Tuesday praising Chapman and his wife, Beth, is important "because it makes clear that people who are clear thinkers and careful about enforcing and making the law are supportive of the Chapmans and what they did," said Brook Hart, Chapman's attorney. "They want justice for the Chapmans, and the more people who want justice for the Chapmans, the more we hope that Mexico will give justice to the Chapmans."

Indeed, Chapman is seen by many Americans as a true hero who brought to justice a despicable serial rapist who had been on the run. Luster was in the habit of incapacitating women with the date-rape drug gamma hydroxybutyrate, or GHB, and was on trial in California when he fled the United States. He was convicted in absentia and now, thanks to Chapman, is serving a 124-year prison sentence.

The perspective from south of the border is somewhat different. Mexican law enforcement still might be smoldering about a 15-year-old U.S. Supreme Court ruling that essentially made American bail-jumpers in Mexico fair game to be caught and hauled back across the Rio Grande. U.S. administrations since then have tried to reduce the friction.

The legal issues concerning extradition are controversial. Although bounty hunting is legal in Hawaii, "that doesn't mean that a bounty hunter can go anywhere in the world to gather up his quarry," said Russell Covey, an assistant professor at the Whittier Law School in Costa Mesa, Calif. "A police officer is authorized to make an arrest in Hawaii but can't go to another country or even another state and arrest people. That would be considered a criminal offense."

Chapman is charged not with kidnapping but with "deprivation of liberty," which may be punishable by as little as six months in jail and as long as four years. If charged at the lower level, he would stand no risk of being extradited for such a minor offense.

The facts also are in dispute concerning Chapman's capture of Luster on June 18, 2003, in Puerto Vallarta, a resort town on Mexico's Pacific coast.

Chapman included in his ranks Timothy Chapman (no relation), son Leland and a man who Chapman claims to have thought was a Mexican police officer who moonlighted as a cab driver. A local law-enforcement official needs to be present during such a capture, and Chapman has said the man, named Filiberto, had shown him his badge and gun as proof of his authority.

However, resort owner Min Labanauskas, who introduced Filiberto to Chapman, has said he is not an officer but merely a cab driver who once was a tourism security guard, according to Kent Black, co-author of Chapman's 2005 book, "You Can Run But You Can't Hide: The Life and Times of Dog the Bounty Hunter."

Filiberto was present when Chapman captured Luster near a taco stand in Puerto Vallarta, and, in his cab, led the caravan destined for what Chapman says he intended to be a police station. According to one account, the car carrying Chapman and Luster was stopped at a roadblock that Filiberto had passed through, two blocks short of the police station and past the airport where he supposedly intended to board Luster for a U.S.-bound plane.

Labanauskas told Black that Filiberto had gone home while the Chapman car mistakenly had followed another cab. Luster and Chapman's entourage were taken into custody at the roadblock.

The 1978 U.S. extradition treaty with Mexico, similar to a treaty with Canada, allows accused offenders to be sent from one country to the other to face justice offenses that are criminal in both countries. A Virginia-based federal appeals court handed over a bounty hunter to Canada in 1983 for his seizure of a bail jumper in that country. Unlike that case, however, Chapman did not bring Luster back to the United States; Mexican police turned Luster over to U.S. authorities.

The United States and Mexico collided over a capture stemming from the 1985 torture and bludgeoning to death of Enrique "Kiki" Camarena Salazar, a U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration agent, in Guadalajara, Mexico. The DEA hired several Mexicans five years later to kidnap Humberto Alvarez-Machain, a Guadalajara physician accused of prolonging Camarena's life so others could further torture and interrogate him. Alvarez challenged the charge against him, maintaining that his abduction in Mexico violated the 1978 extradition treaty between the United States and Mexico.

The Supreme Court rejected Alvarez's argument. In its 1992 ruling, then-Chief Justice William Rehnquist wrote that the treaty "says nothing about the obligations of the United States and Mexico to refrain from forcible abductions of people from the territory of the other nation, or the consequences under the treaty if such an abduction occurs."

Mexican officials were angered by the ruling, and the White House tried to mollify them. President George H.W. Bush quickly gave his assurance in a letter to Mexican President Carlos Salinas that his administration would "neither conduct, encourage nor condone" such transborder abductions from Mexico in the future.

Alan J. Kreczko, then deputy legal adviser to Secretary of State James Baker, said in congressional testimony less than three weeks later that his boss and Mexican Foreign Secretary Fernando Solana exchanged letters "recognizing that transborder abductions by so-called 'bounty hunters' and other private individuals will be considered extraditable offenses by both nations."

Two years later, the two countries' administrations agreed upon such a Treaty to Prohibit Transborder Abductions. However, it defines such abductions as those "by federal, state or local government officials" from the country where the person is wanted "or by private individuals acting under the direction" of government officials. Not only are bounty hunters unaffected by such an agreement, it never was sent to the Senate for ratification.

While post-Bush I administrations might have honored the agreement between Baker and Solana, a judge might ignore it.

"There is a role to play by the executive (branch) in deciding whether or not to extradite somebody," said Covey. "The executive branch has discretion on whether or not to deliver somebody who is found to be extraditable by a judge."

"The defense could argue that this policy does not establish any legal precedent that makes it clear that kidnapping somebody pursuant to bounty hunting is an extraditable offense," Covey added. "The court is still going to have to find that the offense qualifies as one that is extraditable."

In a civil lawsuit in which Alvarez, who later was acquitted, sought redress for his abduction, U.S. District Judge Stephen V. Wilson dismissed a tort claim against the DEA agents on the basis that the abduction was legal. The applicable law, he noted, was that of California, which allows bounty hunters and gives them the right to make a citizen's arrest in Mexico.

The 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals also rejected Alvarez's claim that he was illegally abducted. "The United States does not recognize a prohibition against transborder kidnapping," the appeals panel ruled, "nor can it be said that there is international acceptance of such a norm."

In a footnote in the Supreme Court's 2004 rejection of the Alvarez claim, Justice David H. Souter wrote that Francisco Sosa, one of his abductors, "might well have been liable under Mexican law" despite Wilson's assertion, but the high court did not address the question, which was not at issue in its ruling.

The Supreme Court rejected all of Alvarez's claims for compensation for his detention. "It is enough to hold that a single illegal detention of less than a day, followed by the transfer of custody to lawful authorities and prompt arraignment, violates no norm of customary international law so well-defined as to support the creation of a federal remedy," Souter concluded.

The question might come down to whether the courts view such a brief detention in a criminal case the same as in civil proceedings.

Events affecting Dog Chapman case

The following are key occurrences that might affect the fate of Hawaii bounty hunter Duane "Dog" Chapman, who is facing extradition to Mexico for what authorities there claim was his illegal detention of an American. fugitive within their borders.

» 1978: U.S.-Mexican extradition treaty is signed into law by President Jimmy Carter.

» 1985: U.S. Drug Enforcement Agent Enrique "Kiki" Camarena Salazar is tortured and slain in Mexico.

» 1990: Mexicans hired by the DEA capture Mexican physician Humberto Alvarez-Machain in Guadalajara, Mexico. Alvarez is brought back to the United States to stand trial for his alleged involvement in Salazar's killing.

» 1992: U.S. Supreme Court rules the Alvarez abduction was legal, not in violation of the extradition treaty. Secretary of State James Baker promises no further such abductions by the government or bounty hunters, but the agreement is not incorporated into the treaty.

» 2003: Dog Chapman captures Andrew Luster in Puerto Vallarta, Mexico. Luster is taken by U.S. officials back to serve his prison sentence, and Chapman is charged with deprivation of liberty for detaining Luster.

Compiled by Lee Catterall lcatterall@starbulletin.com |

| |

|