|

|

|

News from Around the Americas | March 2007 News from Around the Americas | March 2007

Once More to the Pentagon

Steve Vogel - Washington Post Steve Vogel - Washington Post

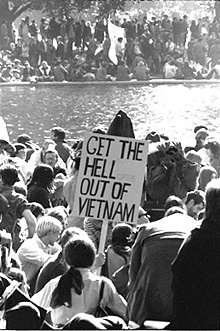

| | Protesting the Vietnam War: The March on the Pentagon, 10/21/1967 (LBJ Library/Frank Wolfe) |

Demonstrators evoke historic confrontation in planning march, rally opposing Iraq War.

At home, the war had reached a turning point. For the first time, a majority of Americans believed the conflict was a mistake. U.S. involvement was nonetheless escalating. Many previous demonstrations had been held, but growing frustration with the political system prompted antiwar leaders to select a new target: the Pentagon.

The 1967 march on the Pentagon to protest the Vietnam War became a touchstone event in American history, one that pitted U.S. citizens against "the true and high church of the military-industrial complex," as marcher and author Norman Mailer put it.

Tomorrow, according to organizers, tens of thousands of demonstrators protesting the war in Iraq will march on the Pentagon in what they are billing as "the 40th anniversary of the historic 1967 march to the Pentagon."

Tomorrow's march, which was scheduled to take place around the fourth anniversary of the start of the Iraq war - March 20 - comes as the Bush administration sends 26,000 additional troops to deal with the violence there. Buses, vans and caravans from across the United States are coming, organizers say, with veterans, soldiers and military family members marching in the first rank of the demonstration. Heading across the Arlington Memorial Bridge to the Pentagon north parking lot, the demonstrators will follow literally in the steps of the earlier protesters. A counter-demonstration in support of the war is also planned for tomorrow.

"The 1967 march wasn't the biggest, but in some ways it's the most historically significant because of the target," said Brian Becker, national coordinator of the ANSWER Coalition, the main sponsor of tomorrow's protest. "It represented a shift in public opinion."

In tying their protest to the Oct. 21, 1967, march, organizers say they are capitalizing on a similar climate among angry voters who believe the results of November elections have been ignored.

Ramsey Clark, who as attorney general for President Lyndon Johnson helped oversee the administration's preparations for the march, said that day shifted the ground under the government. "From that moment, I got the feeling that we'd reached a turning point in the commitment of many people to ending the war in Vietnam," Clark said in an interview this week.

Whether today's feelings match those of 40 years ago is another question. Clark will be among the speakers tomorrow. "I can't tell you that we have the depth of passion or breadth of commitment today that we had then," Clark said.

The 1967 march still raises emotions at both ends of the political spectrum. On the left, it is remembered as a time when peaceful marchers were confronted by bayonet-wielding soldiers and beaten. On the right, the march is recalled as a disgraceful event during which military police were subjected to terrible abuse from protesters.

History shows that both views hold elements of truth. Soldiers manning the line in front of the Pentagon Mall entrance were taunted with vicious slurs and pelted with garbage and fish. Some defenseless protesters sitting peacefully were clubbed and hauled off.

Yet a more complex picture emerges in interviews with demonstrators, Army officers and Pentagon officials responsible for defending the building, as well as research papers in Army archives. Some of the interviews were conducted for a forthcoming book on the history of the Pentagon.

Ironically, Pentagon officials were so preoccupied with presenting a tolerant image that they kept thousands of soldiers hidden inside the building. During the critical early stages of the confrontation, a thin line of MPs outside the building was overrun, and the commander couldn't get reinforcements in place quickly. A subsequent Army report concluded that the low-profile strategy backfired and "may have developed an air of confidence on the part of demonstrators and encouraged violence."

Some protest leaders say they were trying to provoke a confrontation with soldiers in the hopes of escalating the situation. Each side miscalculated, contributing to a bitter confrontation that left a legacy of division.

By that day in October 1967, two years after ground troops were committed to Vietnam, more than 13,000 Americans had been killed and 86,000 wounded. The National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam - an umbrella organization of peace groups and radical organizations - vowed to shut down the Pentagon with the greatest antiwar protest in history.

Among their number was Abbie Hoffman, co-founder of the yippies, who announced plans to levitate the Pentagon 300 feet, using the psychic energy of thousands of protesters.

In addition to 2,400 troops positioned in and around the Pentagon, a brigade from the 82nd Airborne was flown in from Fort Bragg, N.C., and held at Andrews Air Force Base in reserve. More than 12,000 soldiers, National Guard troops, federal marshals and civilian police officers were standing by in the region.

At the order of then-Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara, commanders were operating under restrictions that kept much of the force under wraps. "It was a concern that events would get out of hand, and there would be violence on one side or the other that would lead to continued violence," McNamara recalled in an interview last year.

The march unfolded on a gorgeous autumn Saturday, with 50,000 demonstrators at the Lincoln Memorial. Although in the popular imagination marchers from that era are often recalled as bands of hippies, a large cross section of Americans participated. The majority of the crowd was young and many wore ties, but large numbers of middle-age and older demonstrators were included in the ranks.

Despite claims by organizers of 100,000 or more marchers, counts made by intelligence agencies put the figure of those who continued to the Pentagon at closer to 35,000. Army intelligence later concluded that the protest included "probably fewer than 500 violent demonstrators; however these violent types were backed by from 2,000 to 2,500 ardent sympathizers."

Indeed, much of the protest was peaceful, and the majority of marchers were far removed from any violence. Hoffman, dressed in an Uncle Sam hat and by his own admission tripping on acid, went about his efforts to raise the building by leading protesters in chants.

Shortly before 4 p.m., as the main body of demonstrators arrived on the Pentagon grounds, several hundred radicals raced toward the building. "Our specific goal was to create a confrontation - a nonviolent one, because they were military and we were not - and make a physical effort to get into the Pentagon," Walter Teague, a leader of the group, recalled in an interview.

Army documents show that the operational commander immediately asked for reinforcements from inside the building but had to wait 20 minutes while the request was reviewed by the Justice Department. By then, it was too late. The plaza in front of the Pentagon's Mall entrance was in chaos.

"Our kids were standing there and having all kinds of things thrown at them, to include feces," said Phil Entrekin, then an Army captain commanding a cavalry troop that reinforced the MPs.

In the ensuing melee, several thousand protesters occupied the Mall plaza. Spotting an opening in the Army defense, 30 demonstrators made a break for a Pentagon doorway at 5:30 p.m. The vanguard made it inside before being roughly ejected by troops.

"I think we ought to get some cold steel and start using some gas," Army Chief of Staff Gen. Harold K. Johnson urged, Army records show.

McNamara, after surveying the situation from the Pentagon roof, refused. "Let boredom, hunger and cold take their course," he said.

Nonetheless, late that night, soldiers and federal marshals began clearing the plaza, and many protesters were roughed up in ugly scenes of violence. Four dozen protesters, soldiers and marshals were injured; 683 people were arrested.

Forty years later, the chances of a similar confrontation appear slim.

No soldiers will be deployed to defend the Pentagon this time. The building will be adequately protected by the Pentagon Force Protection Agency, a Pentagon spokeswoman said.

Nor are many protesters likely to get close to the Pentagon in the heightened security atmosphere of post-Sept. 11.

Protest leaders, learning lessons from the 1967 march, said they are taking pains to show no disrespect to soldiers this weekend.

And the Pentagon is not likely to rise in the air. Said Amelia McDonald, a protest organizer, "We're not trying to levitate it." |

| |

|