Mexico City, Mexico — The Mexican government is trying to overhaul the nation’s public schools in a way that might ring familiar in the United States: changing how teachers are hired, fired, and evaluated.

But if teachers unions in the United States were resistant to the idea, some in Mexico are openly hostile.

Hundreds of ski-mask-wearing, rock-throwing, stick-wielding teachers have smashed windows and set fire to the offices of the major political party in the southern state of Guerrero, and thousands are flooding Mexico City, blocking national TV networks, subway lines and, last Wednesday, swarming the roads around Los Pinos, the official residence of the president.

In what has become a fairly common event here, at least 8,000 teachers have set up camp under a sea of nylon tents in Mexico City’s central Zocalo square, where Gumaro Cruz Lopez, an elementary school director from the southern state of Oaxaca, explained his fear that the changes will turn kids into globalized robots at the expense of indigenous culture, free thought, and possibly homemade tacos.

"They want to create one prototype of individual for the sole service of the global socioeconomic system," said Lopez, 51. "They say private companies like Coke, Pepsi, and Bimbo" — one of the world’s largest baking companies —"can help to better our schools, but soon they’ll start bringing all their sodas and snacks and all the little pastries of Bimbo!"

The angry invoking of transnational soda and snack-food companies has to do with the fact that Coca-Cola has built model schools in Mexico, as corporate giants such as Microsoft have gotten involved in US education reform. Union leaders have turned that into a symbol for their fear that some distant authority will soon be telling them how and what to teach.

Political analysts say the fierce resistance also has to do with the fact that the changes directly challenge long-standing union power over jobs.

The overhaul that Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto is pursuing keeps with ideas championed in recent years by former Washington, D.C. schools chancellor Michelle Rhee and others who argue that raising teacher standards is the key to fixing failing schools.

In February, Peña Nieto signed into law the framework for his plan, which would shift the power to hire, fire, and evaluate teachers to the federal government and away from Mexico’s main teachers union, which has been accused of rampant corruption and presiding over a system of awarding jobs in ways that have little to do with merit.

A new system of periodic teacher evaluations is intended to identify incompetent teachers, reward good ones, and set professional standards, with the hope that Mexican students will become more globally competitive.

"In principle, the reforms have a positive spirit," said Miguel Szekely, director of the Institute for Education Innovation. "They are going in the right direction, but implementing them will take time."

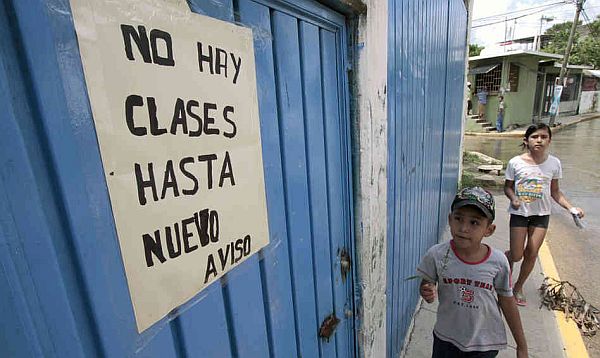

Additional legislation is required to spell out how the system will work. And that is what the massive teacher protests here have stalled, along with traffic.

The emphasis on union corruption — almost universally acknowledged as a huge problem — has to some extent obscured other concerns of the teachers who traveled to Mexico City from some of the poorest states in the southern part of the country. The union that holds sway there is not the one directly targeted by the new education law, but a smaller one that controls jobs and state education budgets and is among the most radical in Mexico.

Rosalia Alonzo, a director of an elementary school in Oaxaca, said any new measures should recognize the disparities between the poorest schools of the south and wealthier ones elsewhere.

"A lot of schools don’t have power or technology, or even books," she said. "The people who come up with these reforms, their kids go to Harvard. They don’t know what it’s like for us."

Pilar Palma, a teacher at the protest, said she suspects that evaluations will be used unfairly. "I agree I should be evaluated," she said. "But give me the tools and the ways to get better."

Lopez, the elementary school director, noted that many students and teachers in his area speak native languages in addition to Spanish. He worries that such particularities will be obliterated by standards handed down from Mexico City.

"Those languages are close to our own customs, to our own environment," Lopez said. "They want to make our children useful as labor for the future of the private sector — to teach them only to work and obey and not to reflect, not to liberate their minds."

Early afternoon last Tuesday, thousands of teachers were heading from the plaza to protest a national TV network they said has been unfairly describing them as a nuisance. The station broadcast interviews with Mexico City residents fed up with the road blockages, people who described the teachers as "dirty" and "those Indians," a reference to their native background. "We are going to block Televisa!" Lopez said, undeterred. "We will be here until the authorities answer us."