|

|

|

Vallarta Living | Art Talk | January 2005 Vallarta Living | Art Talk | January 2005

Frida Kahlo- Forging an Identity

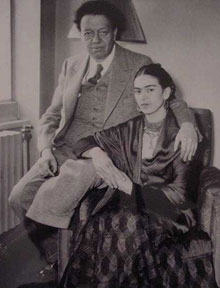

One of the most acknowledged Mexican artists of our time is Frida Kahlo. While it is sometimes difficult to separate the recognition she enjoyed from being the wife of Diego Rivera from her artistic accomplishment, it can be said without question that she was also an important contributor in the development of early modernist art in Mexico. One of the most acknowledged Mexican artists of our time is Frida Kahlo. While it is sometimes difficult to separate the recognition she enjoyed from being the wife of Diego Rivera from her artistic accomplishment, it can be said without question that she was also an important contributor in the development of early modernist art in Mexico.

Born in 1907, Frida grew up in a fashionable residential section of Coyoacan on the outskirts of Mexico City. At the age of six, she contracted polio, which consequently held her back a year in school and left her with an atrophied leg. In spite of this, her father, a German immigrant and professional photographer, encouraged her education by sending her to the National Preparatory School. Born in 1907, Frida grew up in a fashionable residential section of Coyoacan on the outskirts of Mexico City. At the age of six, she contracted polio, which consequently held her back a year in school and left her with an atrophied leg. In spite of this, her father, a German immigrant and professional photographer, encouraged her education by sending her to the National Preparatory School.

As a student at the age of eighteen, another tragedy marked her youth. As a result of a bus and trolley collision her pelvis and spinal column were broken, her foot was crushed, and her body was skewered through the abdomen and uterus by a steel handrail.

These wounds led to lengthy hospital stays, many operations, and, ultimately, her death. During her initial convalescence in 1926, Kahlo began to paint. Over time, this artistic gift enabled her to give meaning to the physical and emotional pain she was to endure.

Legend has it that as a schoolgirl she declared her ambition to marry Diego Rivera. Her aspiration was attained in 1929 when, at the age of twenty-two, Frida married the famous Mexican muralist. Together, they fought for the ideas of Marxism and enjoyed shaping one another's art.

Following a long series of mutual affairs, Frida and Diego divorced ten years after their marriage, only to remarry each other in less than one year. Frida and Diego had no children although Frida was pregnant on several occasions.

Because she had been wounded so severely in the accident, Frida was unable to carry a child to full term and consequently had to have multiple abortions. This created a great deal of sorrow for Frida who desperately wanted to have a child. Because she had been wounded so severely in the accident, Frida was unable to carry a child to full term and consequently had to have multiple abortions. This created a great deal of sorrow for Frida who desperately wanted to have a child.

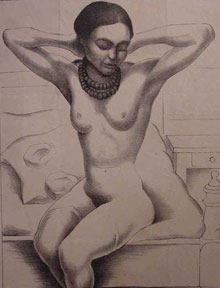

Most of Kahlo's works depict her personal saga: the disabilities she suffered as a result of the accident; her turbulent marriage to Diego Rivera; her involvement with Communism and the Mexican Revolution; and, ultimately, her indomitable will to create.

Like many artists in the decade after the Mexican Revolution of 1917, Frida Kahlo's art was influenced by the surge of nationalism known as Mexicanidad. The simple, naive character of Kahlo's imagery, the fantastic subject matter and the vividness of her colors were influenced by Mexican folk art.

Frida had her first show at an exhibit in the Julien Levy Gallery in New York in 1938. Andre Breton, the famous Surrealist poet and essayist wrote the introduction to the exhibition catalogue, and images from the show appeared in "Vogue" and "Life." It was during this showing that Frida became recognized as an artist in her own right, as opposed to the amateur that she considered herself.

Breton considered Kahlo a self-created Surrealist and admired her subjective symbolism, and the candor and insolence of her self-revelation. In 1939, Breton arranged a group exhibition of Kahlo's and other Mexican artists' works in Paris. In 1940 he organized The International Exhibition of Surrealism at the Gallery of Mexican Art in Mexico City, where Frida's works, "What The Water Gave Me" (1938) and "The Two Fridas" (1939), were exhibited.

The affinities between Kahlo and the Surrealists are evident. Both exhibit a fascination with pain and eroticism, aggression and sexuality, death and procreation; and both approach their subjects with a dark humor, taking pleasure in shocking the sensibilities and standards of decorum. The affinities between Kahlo and the Surrealists are evident. Both exhibit a fascination with pain and eroticism, aggression and sexuality, death and procreation; and both approach their subjects with a dark humor, taking pleasure in shocking the sensibilities and standards of decorum.

Although applauded by the Surrealists as one of their own, Kahlo was reluctant to identify with the movement. Toward the end of her life she astutely observed, " Really I do not know if my paintings are Surrealist or not, but I do know that they are the frankest expression of myself."

Kahlo's hybrid figures and bizarre juxtapositions are not obscure creations or chance encounters dredged up from the subconscious, but deliberately conceived metaphors, which function to express her ideas, perceptions and emotional reality.

Stark, penetrating, and at times violent in their directness, Kahlo's paintings are detached images of her objectified self and experiences. They defined her identity while distracting her from her pain and suffering. Her work was an effort to deal with and give meaning to her tragedy, to her life.

-Denise Deramee |

| |

|