|

|

|

Vallarta Living | Art Talk | December 2005 Vallarta Living | Art Talk | December 2005

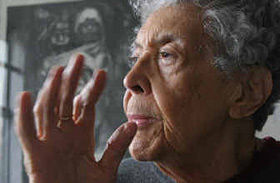

Elizabeth Catlett a Legacy for Artists

Cassandra West - Chicago Tribune Cassandra West - Chicago Tribune

| | Recent news reports about the plight of Asian women being brought into the United States for sexual abuse have stirred Elizabeth Catlett. “I’m going to work that.” |

Although role models who were African-American and female weren’t that plentiful when she was coming along in the 1930s, Elizabeth Catlett held firm to her desire to be an artist.

Yet she did meet an artist who gave her some self-affirming advice. The artist just happened to be white and male. He was Grant Wood, the famous painter and a member of the art department faculty at the University of Iowa, where Catlett did her graduate work. His advice: Take as her subject that which she knows best.

Now, after a long, illustrious career, Catlett has a body of art that stands out because, more than any other artist, she has succeeded in bringing images of black women into the collective canon of modern Western art.

Of course Catlett, 90, knows a lot about black women. Being one herself, she has firsthand understanding of the daily tenor of their lives, their triumphs and pains.

“I feel that black women are the most exploited of anybody,” Catlett said in a telephone interview from New York, where she spends several months each year. “People have the wrong idea about black women. They are either (seen as) a sexual object or an ugly object or a defenseless object.”

Today sculptures and prints by Catlett are in major private collections and museums around the country.

The Art Institute of Chicago recently honored her with its first Legends and Legacy Award in recognition of her “significant and long-standing contributions to the arts.” The event also celebrated the acquisition of five rare Catlett prints, which are being added to the museum’s permanent collection.

Catlett’s “greatest contribution to art is through her prints because they’re the most accessible things she’s made,” said Mark Pascale, associate curator of prints and drawings for the Art Institute. “They underlie the philosophy of all of her work, which is to reach a lot of people with images that speak to social problems and people getting through life, from the very most common person to those who are privileged.”

An exhibition of the five new print acquisitions and four on loan from private local collectors will be on display through Feb. 11.

What Art Institute visitors won’t have a chance to see are Catlett’s sculptures. They make up the bulk of her work and are prized by private collectors and often commissioned as public works.

Her sculptural pieces represent for the most part African-American and Mexican women; the pieces take on social dimensions as they assert “the strength and dignity of these women,” wrote art historian Melanie Anne Herzog in her recently re-released book Elizabeth Catlett: An American Artist in Mexico (University of Washington Press).

Catlett’s sculptures sell in the $150,000 range, said June Kelly, the artist’s New York art dealer. Smaller bronze pieces fetch $30,000. Catlett sculpts mostly hard woods — mahogany and cedar — but works too with limestone, onyx, marble and clay.

Catlett expressed an early interest in art. Her father, a math professor who died before she was born, had left small wood and relief carvings that the young Catlett remembers being around the family’s Washington, D.C., home. Her mother, a teacher who became a truant officer in the Washington public schools, provided Elizabeth with pencils, crayons and paper.

“I just liked to do things with my hands,” Catlett recalled. “When I got to high school, (art) was my favorite class, and when I graduated, I knew I wanted to be an artist.”

After graduating from Howard University in 1935, she moved to Durham, N.C., to teach and supervise art instruction, making $59 a month, or half of what white teachers earned. She fought unsuccessfully along with a young lawyer named Thurgood Marshall — the future Supreme Court justice — to gain equal pay for black teachers.

The next year she was paid a bit more, which allowed her to save for the $75-a-year graduate school tuition at the University of Iowa, where she met Grant Wood and went on to earn the school’s first master of fine arts degree.

Her thesis project, a marble sculpture of a mother and child, won first prize in sculpture at the 1940 American Negro Exposition in Chicago.

For the next two years she taught at Dillard University in New Orleans, spending a summer in between in Chicago studying ceramics at the School of the Art Institute and lithography at the South Side Community Art Center.

Catlett traveled to Mexico in 1946 to complete work on a fellowship. It was the era of the great Mexican muralists Diego Rivera, Jose Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros, and among these artists, she solidified her belief that art could effect social change.

As a guest artist of the Taller de Grafica Popular, or the People’s Graphic Workshop, she learned Spanish, soaked up the culture and fell in love with artist and Taller member Francisco Mora.

The workshop’s “aim was to produce democratic art in favor of the people of Mexico,” Catlett said. It was during this time that she “really got to know poor people,” realizing as well that what she “wanted to do was about black women,” because they had been subjected to so much — poverty, racism, sexism.

During this period, she completed “The Negro Woman,” (1946-47), a series of 15 linoleum cuts and text. One image, titled “I have always worked hard in America,” depicts three African-American women performing the drudgery of domestic work. Those early years in Mexico were intensely productive for Catlett, and she reveled in being among people concerned about social justice. She found personal fulfillment, too, marrying Mora and giving birth to three sons between 1947 and 1951. But Catlett encountered other social-political travails. Her associations with Taller members who supported the Communist Party brought attention from the U.S. Embassy in Mexico. Once, when a massive workers strike was under way, she was seized at her home and spent several days in detention along with others who had been rounded up.

She was released after the secretary of education, who owned some of her work, intervened on her behalf, she said. But for about 10 years in the 1960s and ’70s, she wasn’t allowed to come to the United States.

Catlett “considered Mexican people as her people,” said art historian Samella Lewis, whose 1985 book The Art of Elizabeth Catlett helped renew attention in the U.S. to the artist’s work.

Even as Catlett flourished in Mexico, which granted her citizenship in 1962, she never forgot her African-American heritage. In 1970 she held a major exhibition, “Experiencia negra” (Black Experience), at the Museo de Arte Moderno in Mexico City. Songs by Paul Robeson, Mahalia Jackson and other African-American musical artists played in the background on the opening evening.

Two years ago the International Sculpture Center gave Catlett its Lifetime Achievement in Contemporary Sculpture Award.

She told National Public Radio during an interview just before receiving the award: “What gets me about the States is the lack of culture, people sitting watching television, the hysterical religious groups, the racism, the use of guns — it’s absolutely disgusting.”

After Catlett received the Art Institute Award, she was to return to the home and studio in Cuernavaca, Mexico, that she shared for many years with her husband, who died in 2003.

Her recent stay in the States was perhaps a little longer than she would have preferred, but treatment for the carpal tunnel syndrome that has weakened her left hand prolonged it.

She is anxious to get back to her “wood carving” as she calls it.

But the New York visit has awakened her artistic activism yet again.

TV news reports about Asian women being brought to the United States for sexual abuse disturb her.

“I want to do something now about (the women) on television,” she said. “I’m going to work on that.” |

| |

|