Out of Guatemala Dump: Art, Hope, and Changed Lives

Bernd Debusmann - Reuters Bernd Debusmann - Reuters

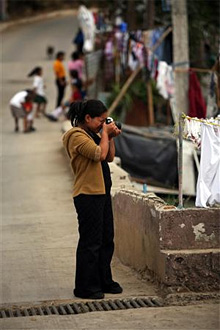

| | Norma Aguilar, from Fotokids, takes pictures in her neighbourhood on the outskirts of Guatemala City February 8, 2006. Fotokids was started by Nancy McGirr in 1991 after McGirr met children scavenging for garbage in the municipal dump while on a journalism assignment. Inspired, McGirr let them take pictures of their world and now Fotokids has grown from the original six to now 85 children, in Guatemala and Honduras. The project has produced riveting photographs shown in exhibitions around the world. (Reuters/Daniel LeClair) |

Guatemala City - It began with an assignment to photograph slum kids, which prompted the idea of letting children scavenging for a living in a municipal garbage dump take pictures of their world. The experiment, unique at the time, was meant to last for six months.

That was in 1991. The experiment turned into a project, Fotokids, that will mark its 15th anniversary this year and has produced riveting photographs shown in exhibitions from Tokyo and Paris to London, Amsterdam and San Francisco.

The project changed the lives of more than 300 families on the margins of society. It also changed the life of the American who founded it, Nancy McGirr.

As a news photographer, she covered the Central American wars, a job that involved taking pictures of people shooting at each other, of weeping survivors, of anger at funerals, of gunmen in masks and of bodies in heaps.

"After a few years of this I got tired of observing, of saying to myself, 'Here's a picture of a problem, I hope somebody will do something about it because I can't.' And move on to the next assignment," McGirr says of the dilemma she eventually resolved by becoming teacher, mentor and second mother to a tribe of children from Guatemala's worst slums.

For most children at the bottom of the ladder, prospects for life are grim. Few make it through elementary school, even fewer complete secondary education.

More often than not, slum children move from sniffing glue to taking drugs, joining street gangs and falling into a life of crime, violence or marginal "employment" - as fire eaters, window shield washers, garbage pickers.

McGirr found a way to break this vicious circle, at least for some, when she noticed that the children she was photographing on that garbage dump assignment 15 years ago were fascinated by her cameras.

"So, what happened after a bit of thinking and a few strokes of good luck was that I handed out cameras to six of the children and told them to start taking photographs. The pictures astonished me," she said. "I knew I had found a way to let them express themselves and give them hope."

OUT OF THE DUMP

Originally known as Out of the Dump, the project resulted in a book of pictures and writings of the same title, published in 1995.

The raw immediacy of the black-and-white images provided an unusual glimpse on a hidden world few readers ever see. The book led to international exhibitions and inspired a number of similar projects around the world.

One of the six children in the original group still works with McGirr. Marta Lopez was 5 when she started taking photographs, many of which showed only the bottom half of her subjects because she was so small she could not aim the camera higher.

Marta is 20 now and an accomplished photographer, veteran of international exhibitions and an assertive woman of big dreams: She wants to found and run a school of her own. Marta is also a role model for the youngest of the present intake of Fotokids, Wilson Santos, aged 7.

Wilson lives at the edge of the municipal dump in a shack made of corrugated iron. His mother makes a living picking through the garbage mountains, complete with medical waste and toxic refuse, that pile up daily a short walk from her home.

Wilson's most valuable possession is a point-and-shoot camera worth $62.

"I take pictures of shadows, and of processions," said Wilson, holding up his silver camera. "I want to become a good photographer."

Marta, who had taken time off from helping prepare a San Francisco exhibition of Fotokids photographs to act as a guide of the dump, smiled at him. "You can do it, Wilson. I did."

Marta's description of the dump, written for the book when she was 9, still stands: "People find many things in the dump. They find shoes, clothing, gold and silver, dresses, earrings, rings, bracelets, dead bodies and strangled children. One day a neighbor lady found a strangled girl in a box "

FOTOKIDS IN HONDURAS. UGANDA NEXT?

Fotokids has grown from the original six to now 85 children, in Guatemala City, two towns in the country's poverty-stricken highlands, and La Ceiba in Honduras.

Most of the other graduates of the program have gone on to productive lives. Along with donated cameras, McGirr keeps the program going by raising sponsorships of $150 or $300 per child a year.

There are now plans to take the concept to Uganda, where McGirr and one of her students, Linda Morales, visited refugee camps recently at the invitation of one of Fotokids' sponsors, World Emergency Relief.

The rules for children who join Fotokids are simple: no glue sniffing, no drugs, no cutting school, good grades. In return, they get classes - after regular school hours - in photography, digital imaging, graphic design, Web site design, creative writing and video.

Plus a daily hot lunch, something few children in the slums can take for granted.

"Back in 1991, I never expected this (project) to become my life. But it did," said McGirr, who left the safety of a staff job with Reuters at the time for the uncertain existence of a freelancer.

"And then, I figured out that you can do things rather than just observe them and that you don't have to know all the answers, and you don't have to work with big numbers of people."

One could also call that "making a difference." One kid at a time.

(GUATEMALA-CHILDREN, editing by Cynthia Osterman; e-mail:Bernd.Debusmann@reuters.com) |